Even thought it has been a while since my last entry on this blog, I have been quite busy. During most of last year I brought my modest contributions into an awesome startup that you have probably heard of by now, helping them integrate GNOME technologies into their products. I was lucky to join their team at an early stage of the development and participate in key discussions.

But more on that project on future entries.

Today I want to talk about things that keep me busy these days, and are of course related to Web engines. Specifically, I want to talk about 2D rasterization and the process of putting pixels on the screen as fast as possible (aka, the 60 frames-per-second holy grail). I want to discuss an idea that has the potential to significantly increase the performance of page rendering by utilizing modern GPU capabilities, OpenGL, and a bit of help from Web engines’ magic.

This is a technical article, so if you are not very familiar with 2D rasterization, OpenGL or how Web engines draw stuff, I recommended you to take some time off and read about it. It is truly a world of wonders (and sometimes pain).

Instanced rendering

The core of the idea is based on instanced rendering. It is a fairly well known technique introduced by OpenGL 3.1 and OpenGL-ES 3.0 as extension GL_EXT_draw_instanced.

To draw geometry with OpenGL, one normally submits a primitive to the rendering pipeline. The primitive consists of a collection of vertices, and a number of attributes per each vertex. Traditionally, you could only submit one primitive at a time.

With instanced rendering, it is possible to send several “instances” of the same primitive (the same collection of vertices and attributes) on a single call. This dramatically reduces the overhead of pipeline state changes and gives the GPU driver a better chance at optimizing rendering of instances of a particular geometry.

Hence, it is generally a common practice for OpenGL applications to group rendering of similar geometry into batches, and submit them to the pipeline all at once as instances. This technique is commonly known as batching and merging.

Skia, the 2D rasterizer used by the Chromium and Android projects, and Cairo, a popular 2D rasterizer backing many projects such as GNOME and previous versions of Mozilla Firefox; both to some extent have support for some sort of instanced rendering in their respective GL backends.

Telling instances apart

Ok, it is possible to draw a bunch of primitives at once, but how can we make them look different? A way of customizing individual instances is necessary, otherwise they will all render on top of the previous one. Not very useful.

There are two ways of submitting per-instance information: one is by adding a “divisor” to the buffers containing vertex or attribute information (VBOs), which will tell the pipeline to use the divided chunks as per-instance information instead of per-vertex. glVertexAttribDivisor is used in this case.

The other way is to upload the per-instance information to a buffer texture (or any texture for that matter) and fetch the information of the corresponding vertex by sampling, using a new variable gl_InstanceID available in shader code, as the key. This variable will increase for each instance of the geometry being rendered (as oppose to per vertex, for which you have gl_VertexID).

So, a quick recap so far. We are able to draw several instances of the same geometry at once, very efficiently, and are able to upload arbitrary data to customize each of these instances at will.

But wait, there are caveats.

The ordering problem

So, lets say we can now group together all drawing operations that involve the same primitive (rectangle, line, circle, etc). What happens if we draw (say) a filled rectangle, then a circle on top, and then another rectangle on top of the circle?

Following the simple grouping rule, what will happen is that the two rectangles will be grouped together and drawn first in one call, then the circle. This will not render the expected result, since the circle will end up laying on top of the rectangle that was drawn after it.

This problem is commonly known as “ordering”, and it clearly breaks our otherwise super-performing batching and merging case.

So, in scenes that involve lots of geometry overlapping, the grouping is limited to contents that do not overlap, if we wanted to preserve the right order of operations.

In practice, it means that we first need to separate the content in layers, then group the same primitives within a single layer, and finally submit the batches from each layer in the right order.

But guess what? Browser engines already do exactly that. Engines build a layer tree (among several other trees) with the information contained in the HTML and CSS content (layout, styling, transformations, etc), where the content is separated in render nodes whose content do not normally overlap. The actual process is much more complicated than that, but this simplification is enough to illustrate the idea.

Now, what if?

First, for the sake of presenting an idea, lets ignore the 2D context of a canvas element by now. More on that later. Lets focus on most of the web sites out there.

If we look at the number of primitives typically used by the rendering of a page, they boil down to a handful. Essentially, they are:

- A rectangle: for almost all HTML elements, which are boxes. And character glyphs! which are normally rendered ahead of time and cached in a texture layout, then texture-mapped onto a rectangle. And images!, which are also texture-mapped onto rectangles.

- A thin line: for thin (<=1 pixel) borders, inset/outset effect, hr, etc. Thicker borders can be drawn as thin rectangles.

- A round corner: the quarter of a circle, filled or stroke, used to implement rounded rectangles (hello border-radius).

- A circle: for bulleted listings, radio-buttons, etc. Argueably, these can be rendered using unicode characters, so no need for specific geometry.

Lets stay with these. There are other cases that I will purposely ignore, like one seen in a rounded rectangle with different thickness in two consecutive borders.

Then we have, for each of these primitives, an evolutionary-like variety of background styles (imaged, colored, repeated, gradient, etc); transformations (rotation, translation, scaling, etc); border styles (again imaged, colored, with different thickness, etc), shadow and blurring effects, and so on.

With a working texture cache, we have a potentially good chance at aggressively grouping together drawing of these primitives, like rectangles for example, for all text glyphs, boxes and images.

So, what if we could submit to a smart shader all the information that describes and tells apart these grouped instances? Is it possible to efficiently pack and then re-interpret in a shader all the styling and transformation complexities of today's CSS-styled HTML elements?

A new approach

Existing 2D rasterizers used in Web engines (at least Skia and Cairo, whose source code is available to me) are general purpose drawing libraries. That means they should render deterministically for any kind of application, not only Web engines. Specifically, they need to avoid the ordering problem explained above, where the result of a set of overlapped drawing operations is different if you change their order.

There are several reasons why modern Web engines use general purpose 2D rasterizers (as opposed to rasterizers written specifically for the needs of Web content rendering). One clear reason is that they existed before (in the case of Cairo at least) as a generic 2D graphics library, and was later used for Web rendering. Other reason is that the implementation of the Canvas 2D spec requires a general purpose 2D API, because that's what it is. And there is a clear benefit in reusing your beautifully optimized Canvas 2D implementation to draw the rest of the Web contents. Also, these libraries evolved from a pixmap (image) backed rendering target, into libraries exploiting the hardware-acceleration of GPU cards. Both libraries now feature an OpenGL(ES) backend that is somehow forced to comply with the previously existing API and behaviors.

But that is sub-optimal for Web engines that simply want to draw non-overlapping content into layers, then draw the layers in order. And even though batching and merging do occur in the GL backends today, it is apparently far from optimal as we will see later.

So, if we completely ignore the ordering problem for the case of Web engines drawing already layered nodes onto an OpenGL based render target, we might be able to aggressively group together potentially all the operations that share the same primitive.

This is of course if, as mentioned above, we are able to describe the particularities of each instance of these primitives, hand them down to a smart shader for rendering, then do all that efficiently so that the performance gained in batching is not lost by uploading tons of instance information to the GPU or running heavy shader code.

It is unclear (to me) whether this is at all possible. That's is why this approach is just an idea yet lacking validation for the real world. But it is a research that could potentially boost performance of Web content rendering.

It shares some similarities with (and was partially inspired by) the way Android does font rendering.

A proof of concept

So, I was set up to write a proof of concept trying to validate or discard the idea as quickly as possible. The purpose is to write the minimum code that would allow meaningful comparison between this approach and exiting rasterizers (Skia being my first target for this), for specific use cases that are relevant to generic Web content rendering (not Canvas 2D).

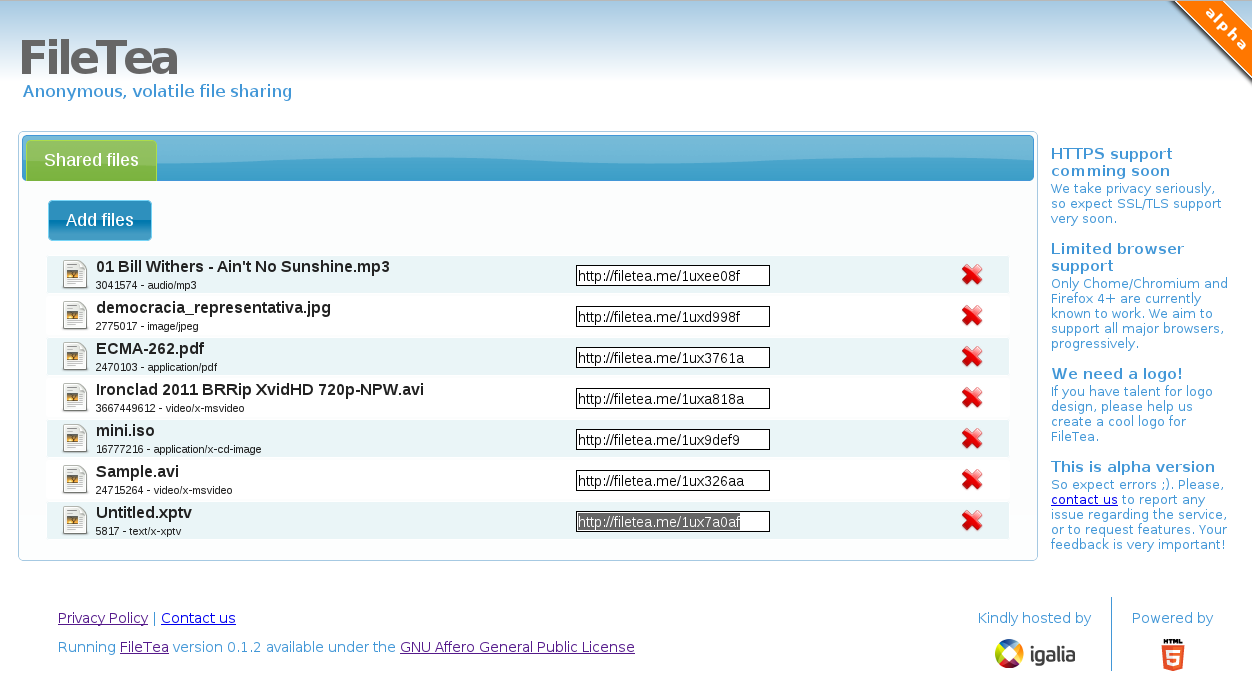

My proof of concept is being developed at: https://github.com/elima/glr

So far, it just provides a few primitives: rectangle and rounded corner, allowing for 3 basic drawing operations: rectangle (filled or stroked), rounded rectangle (only filled) and character glyph (not text, just single characters).

Then each element drawn can be transformed (scaled, rotated and/or translated), laid-out on the canvas (top, left, width and height), and has a color or texture.

Anti-aliasing is achieved by multisampling with 8 samples per pixel. Character glyphs are not anti-aliased, that was too complex to put in a proof of concept and it is a problem already solved by others anyway. I used the simplest possible path to put a pre-cached glyph on the screen, and for that wrote a super naive texture cache, and used FreeType2 for rasterizing the glyphs.

The idea of including chars was to explore if text glyphs, which accounts for most of typical Web page's content, could be batched together with all others drawings that use a rectangle primitive.

Note should be taken that this proof-of-concept is not intended to become a new library. It is just a vehicle to validate an idea by providing the minimum implementation needed to test its limits. Eventually, all this would have to be implemented in existing libraries. I just happen to be very fluent at glib and C :), as to prototype fast.

Comparisons

Before we jump into FPS excitements, lets clarify that any comparison here should be taken with a grain of salt. 2D rasterizers are complex libraries that do a lot of non-trivial things like anti-aliasing, sub-pixel alignment, color space conversion, adaptation to the specifics of the underlying hardware/driver/GL-version combos, to name just a few.

Thus, any comparison should be put in the context of what code paths are being selected, what rendering operations are being grouped, and when and why they aren't; how many GL operations are submitted to the pipeline to render the same scene, etc.

I have included 3 initial examples that try to illustrate how batching and merging of "compatible" draws (sharing the same underlying primitive) improves performance when ordering is ignored, while at the same time each element can have its own color, layout and transformation. For each example, I have written a Skia counterpart that tries to render exactly the same, to the extent possible, for the sake of comparing.

The data below corresponds to runs in my laptop, which is a Thinkpad T440p running Debian GNU/Linux, has an integrated Intel(tm) GPU (4th gen), and the OpenGL driver is provided by Mesa 10.2.1.

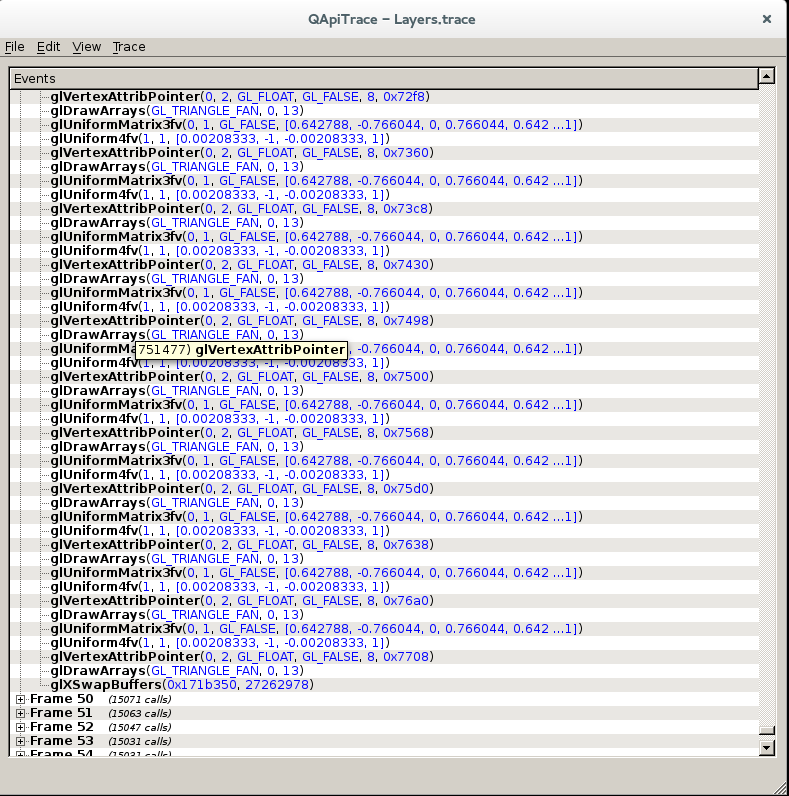

I used apitrace to look at what GL commands are actually sent to the driver.

Lets start with the RectsAndText example. It basically draws a lot of alternating filled rectangles and character glyphs, each with its own color, transformation and layout. In the screencast below, both examples (Skia and glr) are running at the same time. This of course does not reflect real performance since both compete for GPU resources, but I decided to record it this way because the improvement is much better noticed. The frames-per-second decrease proportionally for both examples when run at the same time, so it remains relevant for comparison.

The window in the left corresponds to the Skia example, and the right to glr. The same goes for all screencasts below.

This video file is also available for download.

The difference is considerable. Skia performs at an average of 6-7 FPS while the new approach gives around 40 FPS. That’s a 5x-6x improvement, not bad. Also, notice that CPU usage is considerably higher in the case of Skia.

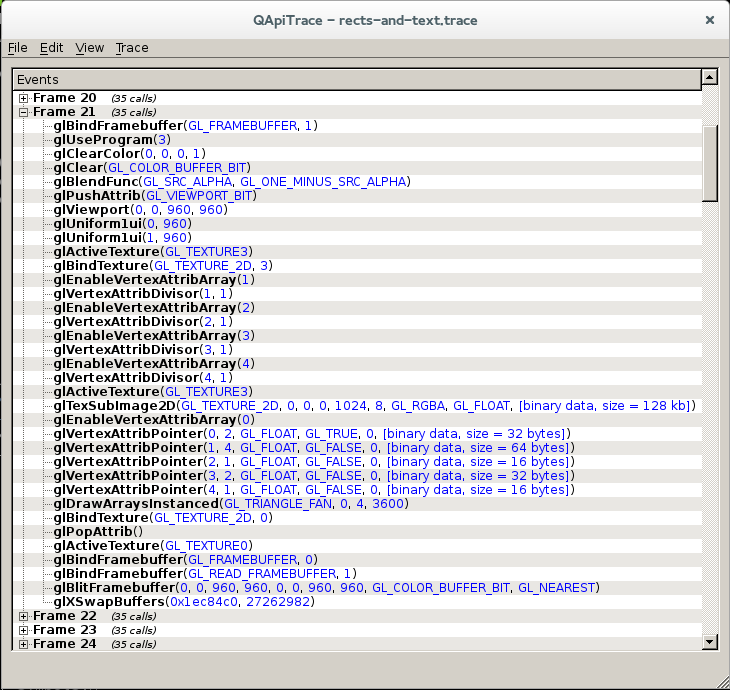

The interesting thing here is that in the case of glr, all elements are batched together (both rectangles and chars), so only one drawing operation is actually submitted to the pipeline, as you can see in the available apitrace dump. A trace for the corresponding Skia example is also available.

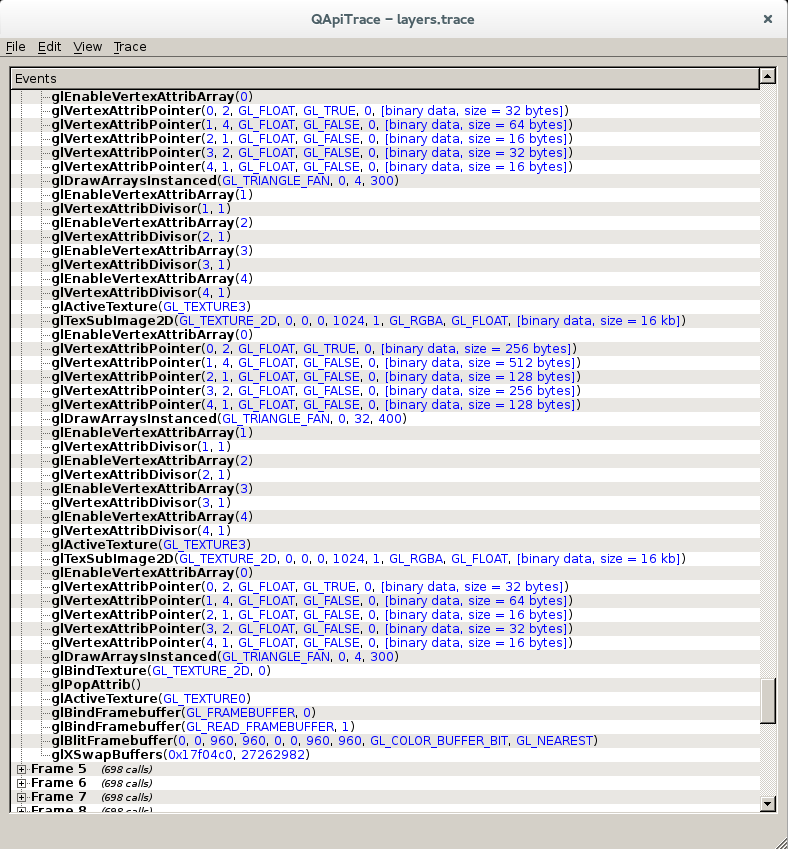

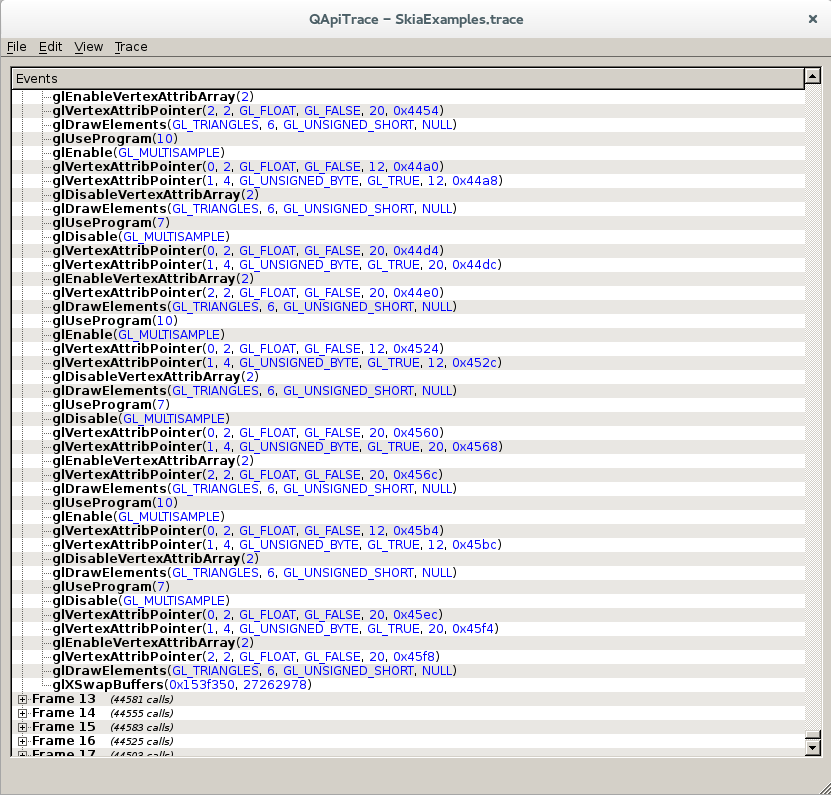

apitrace output for RectAndText glr example

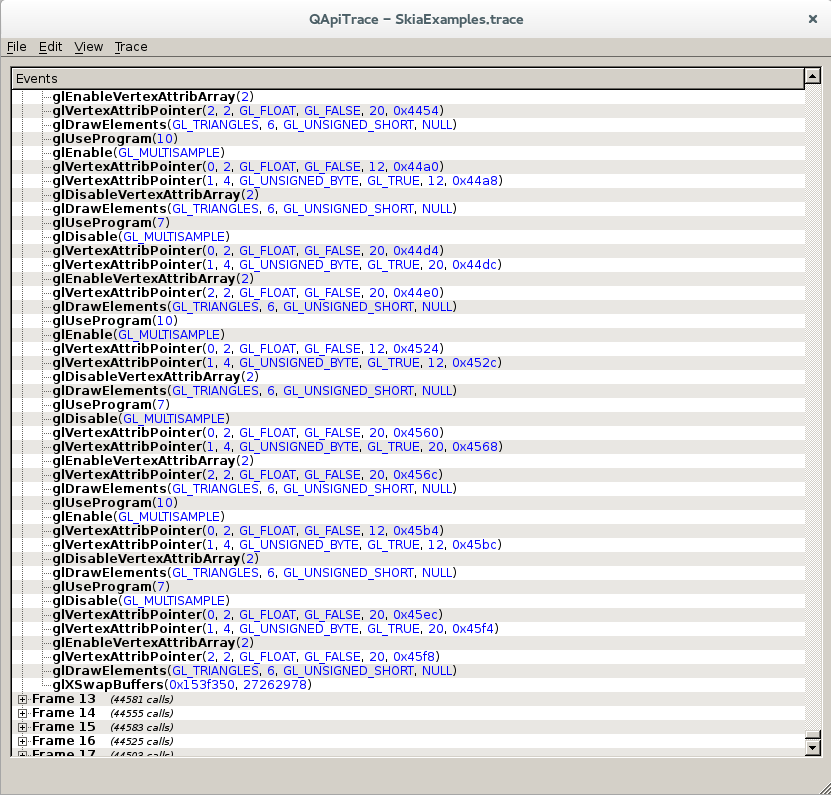

apitrace output for RectAndText Skia example

The next example is Rects, which is similar but renders only rectangles, alternating between filled and stroked. The interesting bit is that in the case of glr, each style of rectangles is drawn onto one different layer, each layer operating on its own separate thread; demonstrating that parallelism is now possible during batching.

This video file is available for download.

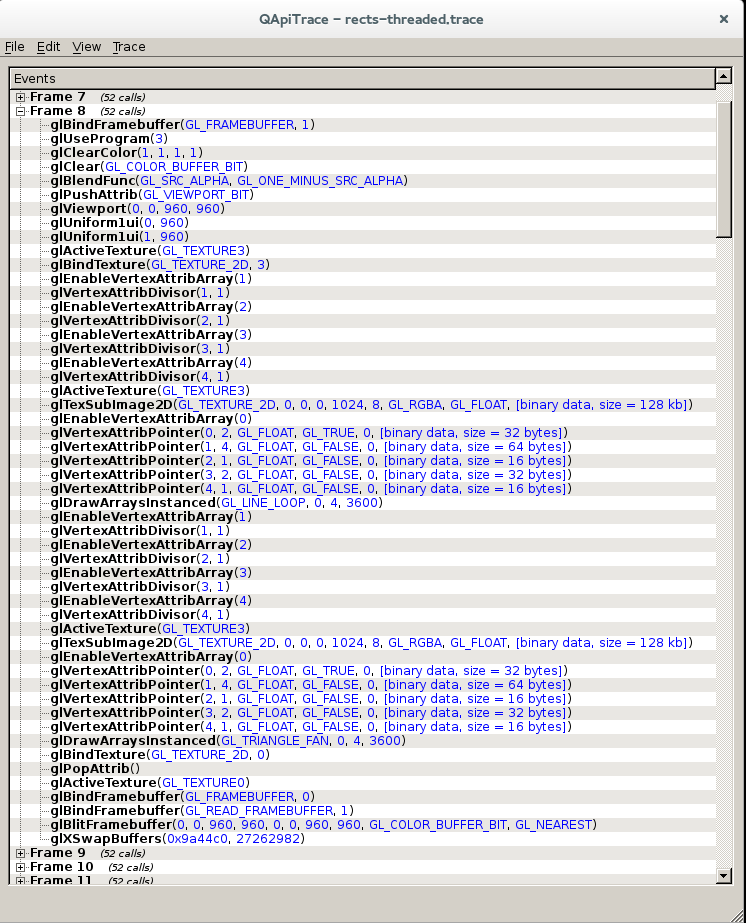

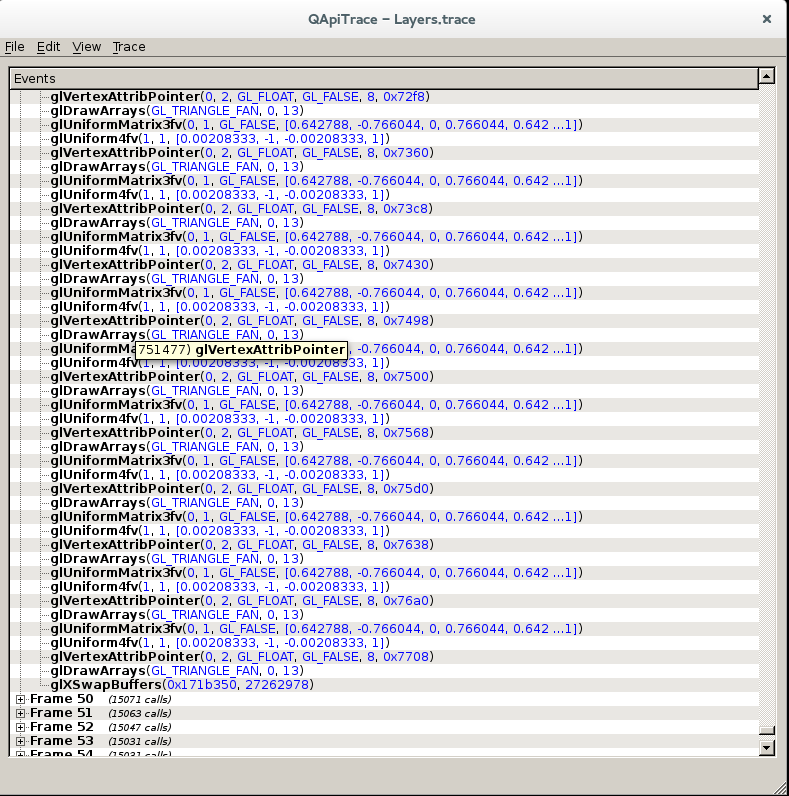

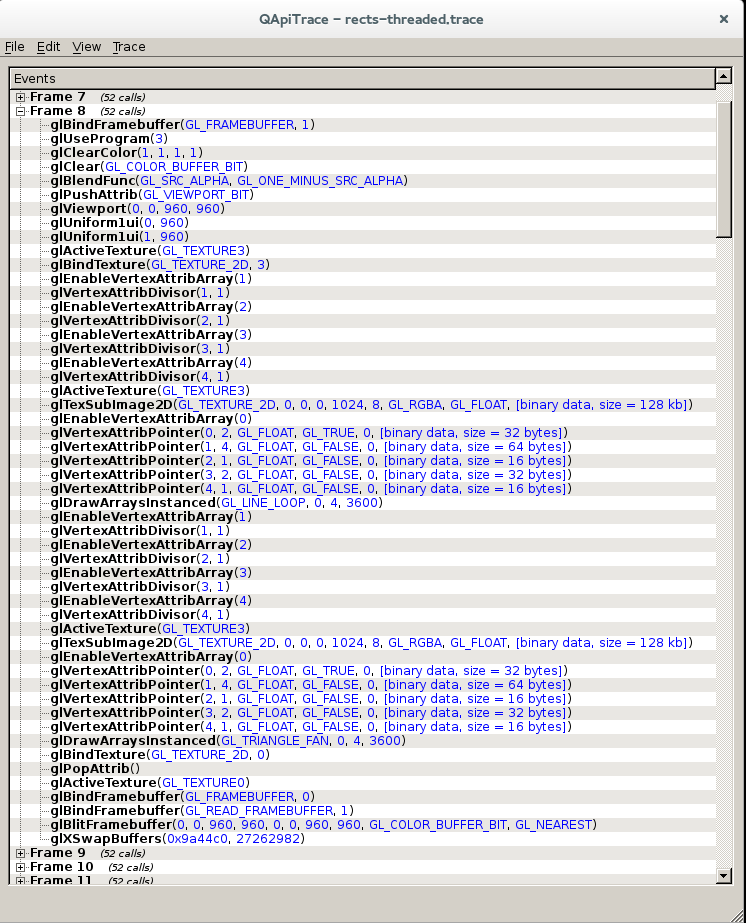

In this example, the performance difference is even higher. glr is around 8x faster. Again, apitrace traces for the glr example and the Skia version are available. This time glr submits a total of 2 instanced drawing operations, one for filled rects and one for stroked.

apitrace output for Rects glr example

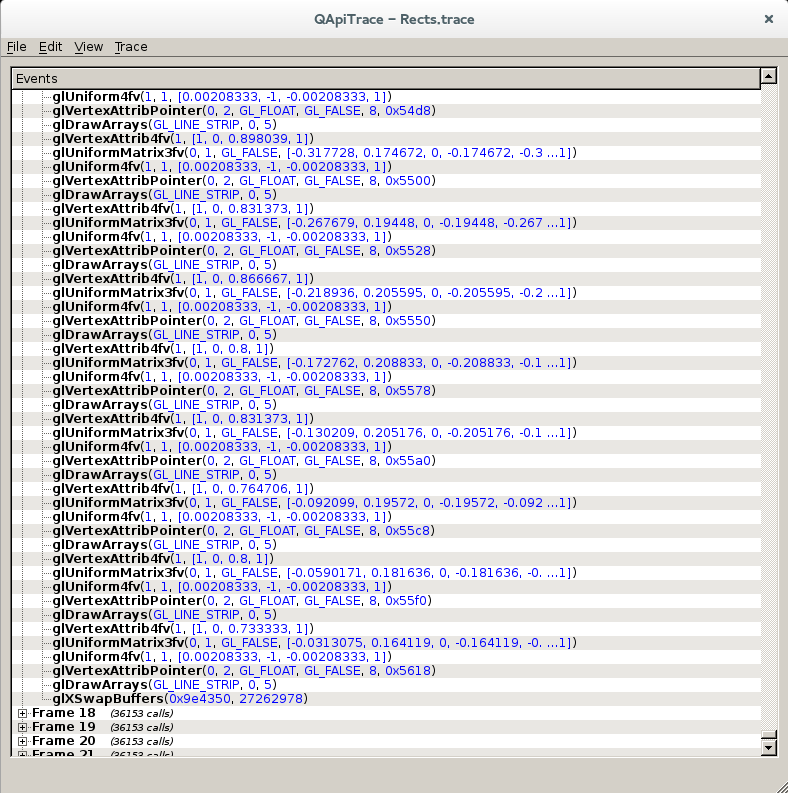

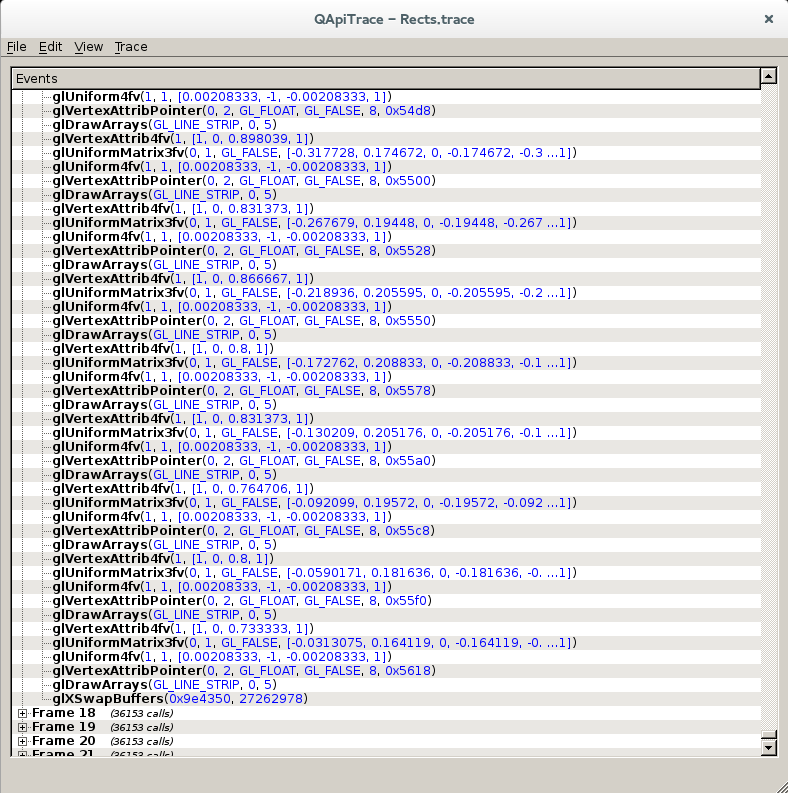

apitrace output for Rects Skia example

The last example draws several layers of non-overlapping rounded rectangles. As with previous examples, every element is given a unique layout, color and transformation. This example tries to illustrate that because batching operates only at layer level, the more layers you have the less you benefit from this technique. In this particular example, the gap is reduced considerably. In fact it looks like Skia is faster by a few FPS, but it is actually not true. When both examples are run together, Skia is faster, but if run separately, glr example is faster (though not much). I’m still figuring this out.

This video file is available for download.

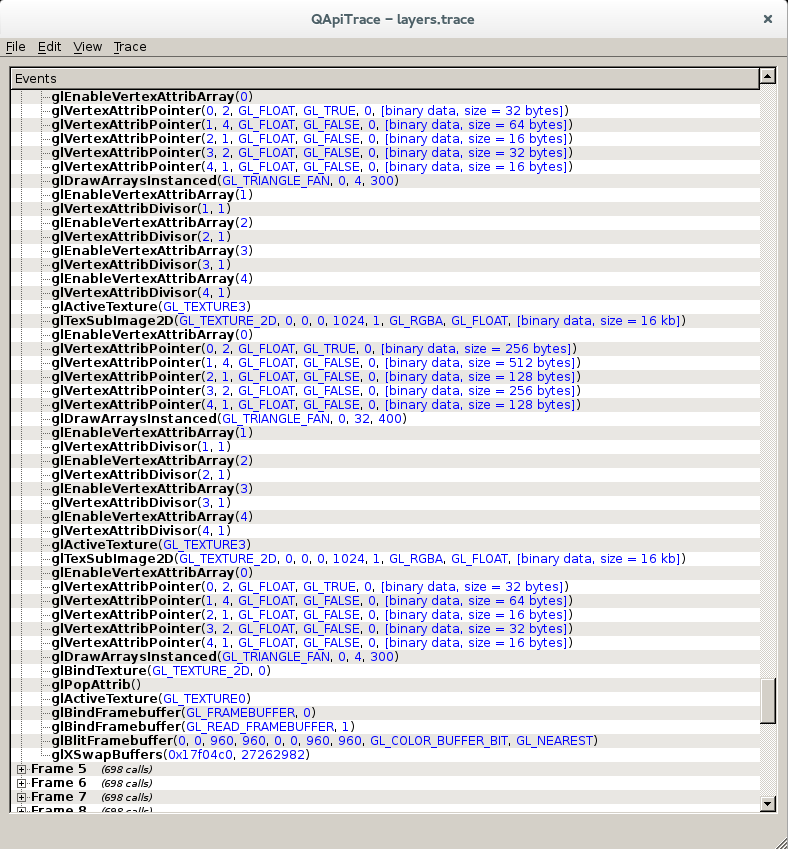

And the traces for the glr example and the Skia example.

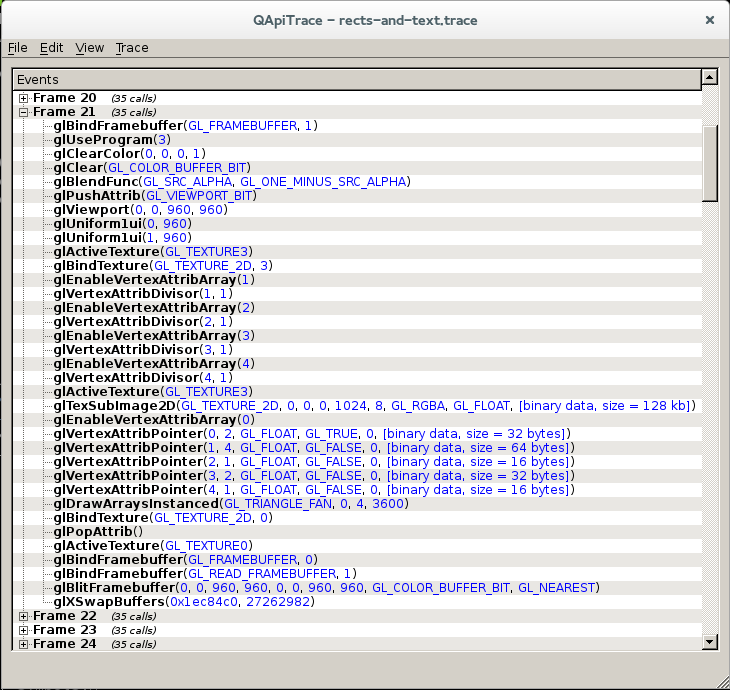

apitrace output for Layers glr example

apitrace output for Layers Skia example

If you are curious about the implementation, take a look at where most of the magic happens: GlrContext, GlrCanvas and GlrBatch objects, and the vertex shader. The rest of the code is mostly API and glue to provide a coherent way to use this approach. Specifically, an abstract concept of "layer" is introduced. The workflow goes this way:

- For initialization, a context, a rendering target and a canvas object are created. This is similar to how other 2D libraries work.

- In the rendering loop and for each frame, the canvas is first notified that a new frame will be rendered.

- Then any number of layer objects are created and attached to the canvas. The drawing API works against a layer (instead of a canvas), and will group and batch all the drawing operations in internal commands. When drawing to a layer finishes, the layer is notified that it is ready.

- Finally, the canvas is requested to finish the frame, right before swapping buffers. This call will wait for all the attached layers to finish (blocking if needed). Once all complete, the canvas will take the batched commands from each layer, in the order they were attached, and submit them to the pipeline for rendering.

One thing to remark is that layers are self-contained stateful objects, and can survive frames without needing to redraw.

Other benefits

One by-product derived from the fact that layers cache drawing operations in internal commands (which in turn use locally allocated buffers), is that layers now become data-parallel. This is a term rarely used in the context of OpenGL because as you probably know, the way its API is designed makes it a giant state machine, making any parallelization unpractical.

With this approach, layers can be drawn in separated threads (or fully moved to OpenCL), which can bring extra performance if there are several complex layers that need drawing at the same time.

Another potential extra benefit comes from the fact that the canvas renders to a target that is actually a framebuffer backed up by a multisample texture. This means we can use any previously rendered frame as a texture, the same way it currently works in both Chromium and Webkit, where layers are texture-mapped then composited into the final scene.

So, we have the flexibility that, if a particular layer is too complex or slow to draw, we can attach it alone to a canvas, render it, and use the texture as with the current model. But, if we are short on texture memory, it is possible to keep commands batched in layers and render them on every frame. This is kind of similar to what Chromium does, recording draw operations into an SkPicture and then re-playing back when needed.

Future work

This is an approach that needs validation for a number of real world use cases before it can be even considered for testing on a Web engine. It is key to explore how complex information (for example, multi-step gradient backgrounds, or complex border styling with rounded rectangles) can be passed to the shaders and rendered correctly and efficiently. Also, there are shadows and blurring effects, all parametrized to cover the most creative use cases, that also need verification against this model.

Basically, we need to understand the limits of the approach by trying to implement modern W3C specs, selecting the most complex features first.

Other important priorities are:

- Understand how much workload can be imposed on shaders side before the gained performance starts to degrade.

- Test on OpenGL-ES and constrained GPU on embedded ARM, to detect the minimum requirements.

- Figure out how to implement a mid-frame flushing mechanism when texture cache exhausts or command buffers get too large. This is not trivial, since to flush a layer (that is possibly running in a separate thread) it has to be blocked, then the canvas has to wait for all layers below it to finish and then execute their commands, then signal the blocked layer to continue.

- Try how scrolling would behave if previously batched layers are drawn for every frame, instead of using current scrolling techniques that rely on rolling big textures, or moving several tiles up and down. These techniques impose either great pressure on texture memory, or a lot of complexity on tile management (or both), specially in the context of new super-high resolution screens.

Conclusions and final words

I have tried to detail an idea that although not new, I believe has not been explored in full in the context of Web engines. It relies on two essential hypothesis:

- That it is possible to batch not only geometry, but the complex attributes of arbitrarily styled HTML elements, and render that geometry as instances using shader code.

- It is safe to ignore ordering of draw operations during rasterization phase, and leverage on Web engine’s layer tree to solve overlapping.

Modern GPUs and OpenGL APIs have great potential for optimizing 2D rasterization, but as it happens most of the times, there is no one solution to fit all. Instead, each particular application and use case requires a different set of strategies and trade-offs for optimum performance.

This approach, even if valid for a sufficient number of use cases is unlikely to go faster than existing approaches for all tests cases. Even less replace these approaches. This is pretty clear in the case of canvas 2D for example, which will continue to require a general purpose rasterizer. But if there is a sufficient number of use cases that would benefit from this approach to some degree, then maintaining one code path that enables it will already be a win.

Finally, I want to thank Samsung SRA for partially sponsoring the time I dedicated to pursue this idea, and also Igalia and igalians which are always there to back me up and help me move forward.

Now, is there anyone interested in helping me explore this idea further?