WPE performance considerations: pre-rendering

This article is a continuation of the series on WPE performance considerations. While the previous article touched upon fairly low-level aspects of the DOM tree overhead, this one focuses on more high-level problems related to managing the application’s workload over time. Similarly to before, the considerations and conclusions made in this blog post are strongly related to web applications in the context of embedded devices, and hence the techniques presented should be used with extra care (and benchmarking) if one would like to apply those on desktop-class devices.

The workload #

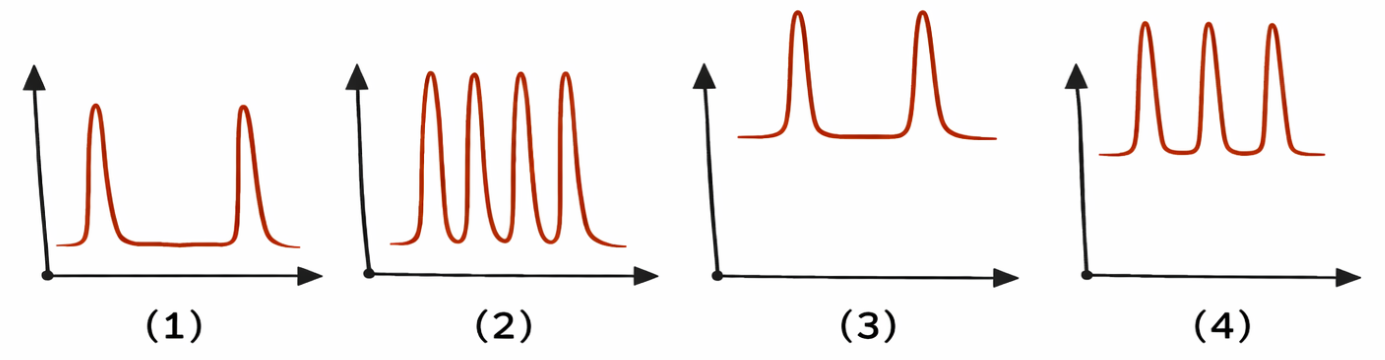

Typical web applications on embedded devices have their workloads distributed over time in various ways. In practice, however, the workload distributions can usually be fitted into one of the following categories:

- Idle applications with occasional updates - the applications that present static content and are updated at very low intervals. As an example, one can think of some static dashboard that presents static content and switches the page every, say, 60 seconds - such as e.g. a static departures/arrivals dashboard on the airport.

- Idle applications with frequent updates - the applications that present static content yet are updated frequently (or are presenting some dynamic content, such as animations occasionally). In that case, one can imagine a similar airport departures/arrivals dashboard, yet with the animated page scrolling happening quite frequently.

- Active applications with occasional updates - the applications that present some dynamic content (animations, multimedia, etc.), yet with major updates happening very rarely. An example one can think of in this case is an application playing video along with presenting some metadata about it, and switching between other videos every few minutes.

- Active applications with frequent updates - the applications that present some dynamic content and change the surroundings quite often. In this case, one can think of a stock market dashboard continuously animating the charts and updating the presented real-time statistics very frequently.

Such workloads can be well demonstrated on charts plotting the browser’s CPU usage over time:

As long as the peak workload (due to updates) is small, no negative effects are perceived by the end user. However, when the peak workload is significant, some negative effects may start getting noticeable.

In case of applications from groups (1) and (2) mentioned above, a significant peak workload may not be a problem at all. As long as there are no continuous visual changes and no interaction is allowed during updates, the end-user is unable to notice that the browser was not responsive or missed some frames for some period of time. In such cases, the application designer does not need to worry much about the workload.

In other cases, especially the ones involving applications from groups (3) and (4) mentioned above, the significant peak workload may lead to visual stuttering, as any processing making the browser busy for longer than 16.6 milliseconds will lead to lost frames. In such cases, the workload has to be managed in a way that the peaks are reduced either by optimizing them or distributing them over time.

First step: optimization #

The first step to addressing the peak workload is usually optimization. Modern web platform gives a full variety of tools to optimize all the stages of web application processing done by the browser. The usual process of optimization is a 2-step cycle starting with measuring the bottlenecks and followed by fixing them. In the process, the usual improvements involve:

- using CSS containment,

- using shadow DOM,

- promoting certain parts of the DOM to layers and manipulating them with transforms,

- parallelizing the work with workers/worklets,

- using the

visibilityCSS property to separate painting from layout, - optimizing the application itself (JavaScript code, the structure of the DOM, the architecture of the application),

- etc.

Second step: pre-rendering #

Unfortunately, in practice, it’s not uncommon that even very well optimized applications still have too much of a peak workload for the constrained embedded devices they’re used on. In such cases, the last resort solution is pre-rendering. As long as it’s possible from the application business-logic perspective, having at least some web page content pre-rendered is very helpful in situations when workload has to be managed, as pre-rendering allows the web application designer to choose the precise moment when the content should actually be rendered and how it should be done. With that, it’s possible to establish a proper trade-off between reduction in peak workload and the amount of extra memory used for storing the pre-rendered contents.

Pre-rendering techniques #

Nowadays, the web platform provides at lest a few widely-adapted APIs that provide means for the application to perform various kinds of pre-rendering. Also, due to the ways the browsers are implemented, some APIs can be purposely misused to provide pre-rendering techniques not necessarily supported by the specification. However, in the pursuit of good trade-offs, all the possibilities should be taken into account.

Before jumping into particular pre-rendering techniques, it’s necessary to emphasize that the pre-rendering term used in this article refers to the actual rendering being done earlier than it’s visually presented. In that sense, the resource is rasterized to some intermediate form when desired and then just composited by the browser engine’s compositor later.

Pre-rendering offline #

The most basic (and limited at the same time) pre-rendering technique is one that involves rendering offline i.e. before the browser even starts. In that case, the first limitation is that the content to be rendered must be known beforehand. If that’s the case, the rendering can be done in any way, and the result may be captured as e.g. raster or vector image (depending on the desired trade-off). However, the other problem is that such a rendering is usually out of the given web application scope and thus requires extra effort. Moreover, depending on the situation, the amount of extra memory used, the longer web application startup (due to loading the pre-rendered resources), and the processing power required to composite a given resource, it may not always be trivial to obtain the desired gains.

Pre-rendering using canvas #

The first group of actual pre-rendering techniques happening during web application runtime is related to Canvas and OffscreenCavas. Those APIs are really useful as they offer great flexibility in terms of usage and are usually very performant. However, in this case, the natural downside is the lack of support for rendering the DOM inside the canvas. Moreover, canvas has a very limited support for painting text — unlike the DOM, where CSS has a significant amount of features related to it. Interestingly, there’s an ongoing proposal called HTML-in-Canvas that could resolve those limitations to some degree. In fact, Blink has a functioning prototype of it already. However, it may take a while before the spec is mature and widely adopted by other browser engines.

When it comes to actual usage of canvas APIs for pre-rendering, the possibilities are numerous, and there are even more of them when combined with processing using workers. The most popular ones are as follows:

- rendering to an invisible canvas and showing it later,

- rendering to a canvas detached from the DOM and attaching it later,

- rendering to an invisible/detached canvas and producing an image out of it to be shown later,

- rendering to an offscreen canvas and producing an image out of it to be shown later.

When combined with workers, some of the above techniques may be used in the worker threads with the rendered artifacts transferred to the main for presentation purposes. In that case, one must be careful with the transfer itself, as some objects may get serialized, which is very costly. To avoid that, it’s recommended to use transferable objects and always perform a proper benchmarking to make sure the transfer is not involving serialization in the particular case.

While the use of canvas APIs is usually very straightforward, one must be aware of two extra caveats.

First of all, in the case of many techniques mentioned above, there is no guarantee that the browser will perform actual rasterization at the given point in time. To ensure the rasterization is triggered, it’s usually

necessary to enforce it using e.g. a dummy readback (getImageData()).

Finally, one should be aware that the usage of canvas comes with some overhead. Therefore, creating many canvases or creating them often, may lead to performance problems that could outweigh the gains from the pre-rendering itself.

Pre-rendering using eventually-invisible layers #

The second group of pre-rendering techniques happening during web application runtime is limited to the DOM rendering and comes out of a combination of purposeful spec misuse and tricking the browser engine into making it rasterizing on demand. As one can imagine, this group of techniques is very much browser-engine-specific. Therefore, it should always be backed by proper benchmarking of all the use cases on the target browsers and target hardware.

In principle, all the techniques of this kind consist of 3 parts:

- Enforcing the content to be pre-rendered being placed on a separate layer backed by an actual buffer internally in the browser,

- Tricking the browser’s compositor into thinking that the layer needs to be rasterized right away,

- Ensuring the layer won’t be composited eventually.

When all the elements are combined together, the browser engine will allocate an internal buffer (e.g. texture) to back the given DOM fragment, it will process that fragment (style recalc, layout), and rasterize it right away. It will do so

as it will not have enough information to allow delaying the rasterization of the layer (as e.g. in case of display: none). Then, when the compositing time comes, the layer will turn out to be invisible in practice

due to e.g. being occluded, clipped, etc. This way, the rasterization will happen right away, but the results will remain invisible until a later time when the layer is made visible.

In practice, the following approaches can be used to trigger the above behavior:

- for (1), the CSS properties such as

will-change: transform,z-index,position: fixed,overflow: hiddenetc. can be used depending on the browser engine, - for (2) and (3), the CSS properties such as

opacity: 0,overflow: hidden,contain: strictetc. can be utilized, again, depending on the browser engine.

The scrolling trick

While the above CSS properties allow for various combinations, in case of WPE WebKit in the context of embedded devices (tested on NXP i.MX8M Plus), the combination that has proven to yield the best performance benefits turns

out to be a simple approach involving overflow: hidden and scrolling. The example of such an approach is explained below.

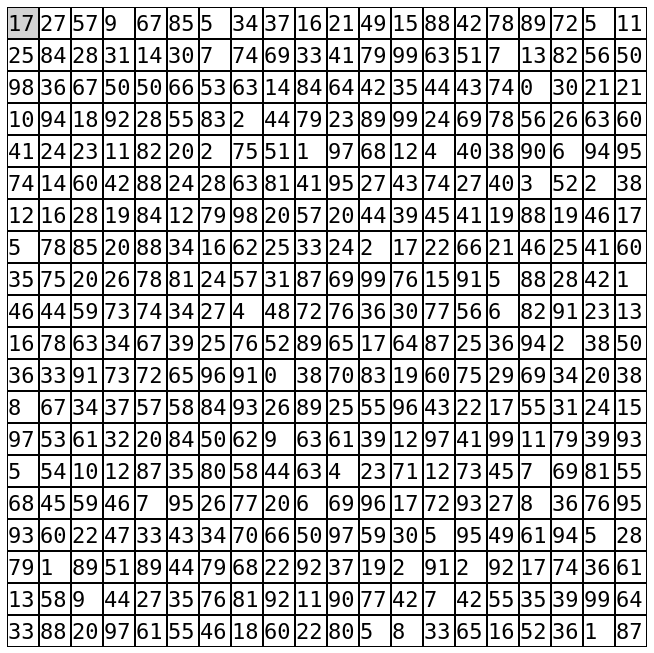

Suppose the goal of the application is to update a big table with numbers once every frames — like in the following demo: random-numbers-bursting-in-table.html?cs=20&rs=20&if=59

With the number of idle frames (if) set to 59, the idea is that the application does nothing significant for the 59 frames, and then every 60th frame it updates all the numbers in the table.

As one can imagine, on constrained embedded devices, such an approach leads to a very heavy workload during every 60th frame and hence to lost frames and unstable application’s FPS.

As long as the numbers are available earlier than every 60th frame, the above application is a perfect example where pre-rendering could be used to reduce the peak workload.

To simulate that, the 3 variants of the approach involving the scrolling trick were prepared for comparison with the above:

- random-numbers-bursting-in-table-prerendered-1.html?cs=20&rs=20&if=59

- random-numbers-bursting-in-table-prerendered-2.html?cs=20&rs=20&if=59

- random-numbers-bursting-in-table-prerendered-3.html?cs=20&rs=20&if=59

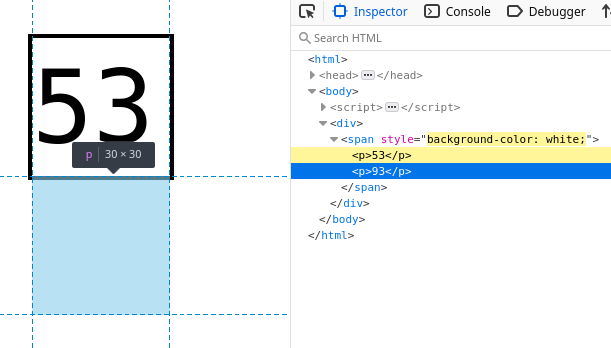

In the above demos, the idea is that each cell with a number becomes a scrollable container with 2 numbers actually — one above the other. In that case, because overflow: hidden is set, only one of the numbers is visible while the

other is hidden — depending on the current scrolling:

With such a setup, it’s possible to update the invisible numbers during idle frames without the user noticing. Due to how WPE WebKit accelerates the scrolling, changing the invisible numbers, in practice, triggers the layout and rendering right away. Moreover, the actual rasterization to the buffer backing the scrollable container happens immediately (depending on the tiling settings), and hence the high cost of layout and text rasterization can be distributed. When the time comes, and all the numbers need to be updated, the scrollable containers can be just scrolled, which in that case turns out to be ~2 times faster than updating all the numbers in place.

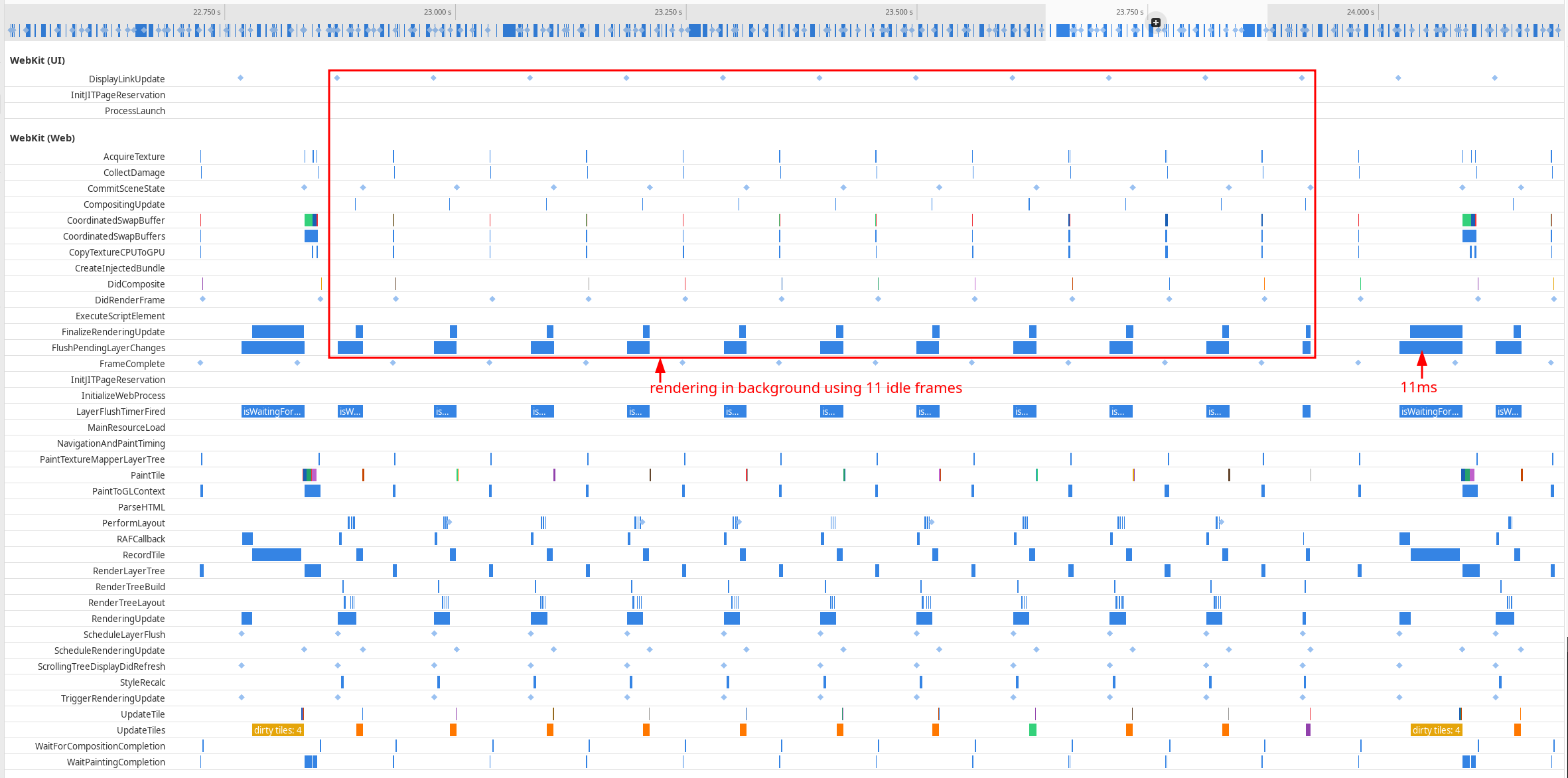

To better understand the above effect, it’s recommended to compare the mark views from sysprof traces of the random-numbers-bursting-in-table.html?cs=10&rs=10&if=11 and random-numbers-bursting-in-table-prerendered-1.html?cs=10&rs=10&if=11 demos:

While the first sysprof trace shows very little processing during 11 idle frames and a big chunk of processing (21 ms) every 12th frame, the second sysprof trace shows how the distribution of load looks. In that case, the amount of work during 11 idle frames is much bigger (yet manageable), but at the same time, the formerly big chunk of processing every 12th frame is reduced almost 2 times (to 11 ms). Therefore, the overall frame rate in the application is much better.

Results

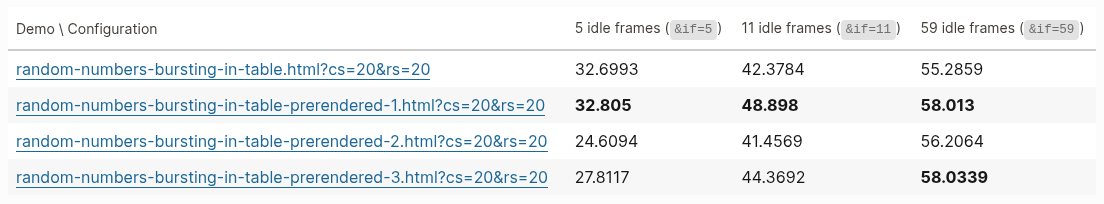

Despite the above improvement speaking for itself, it’s worth summarizing the improvement with the benchmarking results of the above demos obtained from the NXP i.MX8M Plus and presenting the application’s average frames per second (FPS):

Clearly, the positive impact of pre-rendering can be substantial depending on the conditions. In practice, when the rendered DOM fragment is more complex, the trick such as above can yield even better results. However, due to how tiling works, the effect can be minimized if the content to be pre-rendered spans multiple tiles. In that case, the browser may defer rasterization until the tiles are actually needed. Therefore, the above needs to be used with care and always with proper benchmarking.

Conclusions #

As demonstrated in the above sections, when it comes to pre-rendering the contents to distribute the web application workload over time, the web platform gives both the official APIs to do it, as well as unofficial means through purposeful misuse of APIs and exploitation of browser engine implementations. While this article hasn’t covered all the possibilities available, the above should serve as a good initial read with some easy-to-try solutions that may yield surprisingly good results. However, as some of the ideas mentioned above are very much browser-engine-specific, they should be used with extra care and with the limitations (lack of portability) in mind.

As the web platform constantly evolves, the pool of pre-rendering techniques and tricks should keep evolving as well. Also, as more and more web applications are used on embedded devices, more pressure should be put on the specification, which should yield more APIs targeting the low-end devices in the future. With that in mind, it’s recommended for the readers to stay up-to-date with the latest specification and perhaps even to get involved if some interesting use cases would be worth introducing new APIs.