Since January, Igalia has been working on a project whose goal is to make the latest Chromium Browser able to run natively on Wayland-based environments. The project has various phases, requires us to carve out existing implementations and align our work with the direction Chromium’s mainline is taking.

In this post I will provide an update on the progresses we have made over 2017/H1, as well as our plans coming next.

In order to jump straight to the latest results section (including videos) without the details, click here.

Background

In 2016/Q4, my fellow Igalian Frédéric Wang and I ran a warm-up project to check the status of the existing Wayland support in Chromium’s mainline repository, and estimate how much work was needed to get the full (and latest) Chromium browser running on Wayland.

As part of this warm-up we were able to build and launch ChromeOS’s Chrome for both desktop and embedded Linux distributions, featuring either X11 or Wayland. Automotive Grade Linux running on the Renesas’ R-car M3 board is an example of the embedded environments we tested.

Although this was obviously not our end goal (some undesirable ChromeOS widgets were visible at the bottom), it allowed us to verify the overall performance of the build, and experiment with things a bit. Here is a brief summary of the most relevant findings:

- There is an ongoing effort to reimplement the Ash (aka “cash” or classic Ash) Window Manager on top of the new UI Service (aka Mus). It is the so called mus+ash project, a ChromeOS oriented effort that is the continuation of Mandoline project.

-

It is possible to build mus+ash for various platforms including Linux, ChromeOS and Windows. On Linux specifically, it is possible to make off-device ChromeOS builds of mus+ash, and run it on desktop Linux for testing purposes. A more minimalistic Window Manager version is also available in //mash/simple_wm, and should run on regular Linux builds too.

-

mus+ash can be built with Ozone enabled. This means that it can run with the various backends Ozone has. It is worth saying that the upstream focus seems to be the Ozone/DRM-GBM backend, for ChromeOS.

-

Ozone itself has morphed over time from an abstraction layer underneath the Aura toolkit, to be a layer underneath Mus.

Last, we could publish some worth reading content:

- Analysis of Ozone/Wayland – by fwang.

- Chromium, Ozone, Wayland and beyond – by tonikitoo.

- Chromium on R-car M3 (Renesas) board – by fwang.

- Mus window system – by fwang.

2017 developments

At the beginning of this new phase of the project, we knew we needed to work on two different levels, in order to have the Chromium browser running on desktop Linux, ideally without functionality losses if compared against the stock Chromium browser on X11: both Mus and Ozone needed to support ‘external window’ mode.

For the sake of completeness, the term external window mode above is the terminology we chose to represent a regular desktop application on Linux, where the host Window Manager takes care of windowing actions like maximize, minimize, restore and fullscreen the application window. Also, the application itself reacts to content size changes accordingly. Analogously, when we say an application runs in internal window mode, it runs within the (M)ash shell environment, the builtin Window Manager that powers ChromeOS builds. Applications in this mode do not interact with the host WM.

A huge pro about how mus+ash is being implemented is that the Chrome browser itself already works as it ought to in non-ChromeOS Mus-based environments: either we are running Mus in internal or external window modes, Chrome will work just like Chrome for a Linux desktop ought to.

That being said, we identified the following set of tasks, on both Ozone and Mus sides.

Ozone tasks:

- Extend Ozone so that both Window Manager provided window decorations (like a regular X11 window on Ubuntu) and Chromium’s builtin window decoration work flawlessly.

- On Wayland, window decorations can be provided either by the client side (application), or by the Wayland server (compositor). The fact that Weston does not provide window decorations by default, forces us to support Chromium’s builtin one for the good.

- In case of the Chromium’s builtin window decorations …

- … add support for basic windowing functionality like maximize, minimize, restore and fullscreen, as well as window dragging and resizing.

- Add support to “window close”.

- In internal window mode, there is no concept of window closing, because the outer/native Ozone window represents the Window Manager display, which is not supposed to get closed. In external window mode, windows can be closed freely, as per the needs of the user.

- Add support for multi window browsing.

- Each browser window should be backed by its own acceleratedWidget. This also includes being able to draw widgets that on stock Linux/X11 builds use native windows: tooltips, (nested and context) menus.

- Handle keyboard focus activation when switching windows.

- Again in ‘internal window’ mode the outer/native Ozone window is unique and represents the Window Manager display, not losing or gaining focus at any time. Focus switching of inner windows is handled by mus+ash. In ‘external window’ mode, user can open as many Browser windows as he wants, and focus switches at the Window Manager level, should reflect on the application focus.

Mus tasks:

- Fix assumptions that make sense for mus+ash on ChromeOS only.

- The fact that a display::Display instance mapped always to a single ui::ws::Display instance.

- Ownership model

- Some Mus objects have slightly different ownership in external window mode: ws::Display, ws::WindowManagerState, ws::WindowManagerDisplayRoot and ws::WindowTree

The plan

After meeting with rjkroege@ at BlinkOn 7, we defined a highlevel plan to tackle the project. These were the main action points:

1) Extend the mus_demo to work in ‘external window’ mode.

2) Start fixing 1:1 assumptions in the code, e.g. display::Display ui::ws::Display.

3) Extend Mus to work on ‘external window’ mode.

4) Extend Ozone to work on ‘external window’ mode.

5) Make the code that handles the existing –mus command line parameter non-ChromeOS specific.

With this 5 highlevel steps done, we would be able to get Chrome/Mus running on desktop Linux, on the various Ozone backends.

The action

Mus Demo

We were able to get mus_demo working in ‘external window’ mode, by making use of the existing WindowTreeHostFactory API.

1:1 assumptions

Although WindowTreeHostFactory was in place for the creation WindowTreeHost instances, both Mus and Ozone still had assumptions that only applied in a ChromeOS context. The Googler kylechar@ jumped in and fixed some of them, helping out on our effort.

Mus and Ozone carve out

In order to get the 3rd and 4th steps going, we decided to switch our main development repository to a GitHub fork, so that we could expedite reviews and progresses. Given Igalia’s excellence in carrying downstream forks of large projects forward, we established a contribution process and a rebase strategy that would allow us to move at a good pace, and still stay as close as possible to Chromium’s tip of trunk.

These are some of the main changes in our downstream repository:

- Mus and Aura/Mus were changed to support an ‘external window’ mode flow: there is a single WindowTreeClient (Aura/Mus) instance that maps to another single WindowTree instance (Mus). The relationship is invariable and is ensured by ui::ws::WindowTreeHostFactoryRegistrar class.

-

In this new set up, ui::ws::WindowTreeHostFactory::CreatePlatformWindow can create as many WindowTreeHost / ui::ws::Display instances as needed. ui::ws::Display triggers creation of PlatformDisplay objects, which hold Ozone window handles. Hence, every Chromium window (and some browser widgets) gets backed by its own acceleratedWidget.

-

In mus+ash, there are some operations accomplished through a cooperation between both Mus and Ash, or Mus and Aura/Mus sides. For example, setting “frame decorations” values in mus+ash goes through the following path:

1) ash::mus::WindowManager get frame decoration values as per the “material design” in use and passes it to aura::WindowTreeClient::SetFrameDecorationValues.

2) WindowTree::WmSetFrameDecorationValues

3) WindowManagerState::SetFrameDecorationValues

4) UserDisplayManager::OnFrameDecorationValuesChanged

5) ScreenMus::OnDisplays()

6) These values are used later on to draw “non client frame” area of the Browser window, which “frame” that contains the Web contents area.On Chrome/Mus LinuxOS, we skip this round trip by using the same “non client frame view” as stock Linux/X11 Chrome: OpaqueBrowserFrameView.

-

In mus+ash all Browser widgets creation take the DesktopNativeWidgetAura path. This implies a new WindowPort and new WindowTreeHost instances per widget. Adding support for this in Mus and Ozone sides would require lots of work and refactory. Hence, we again decided to use the stock Linux/X11 flow: for widgets currently backed by a native window (tooltips, menus) we use the NativeWidgetAura path, whereas for others widgets (bookmark banner and zoom in/out banners, URL completion window, status bubble, etc) we use NativeWidgetAura. Also, this choice made extending Ozone accordingly simpler.

Status and next steps

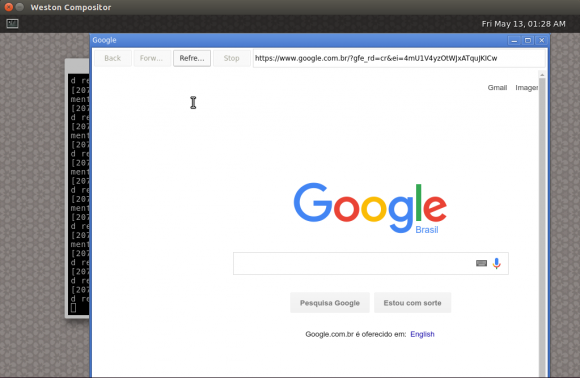

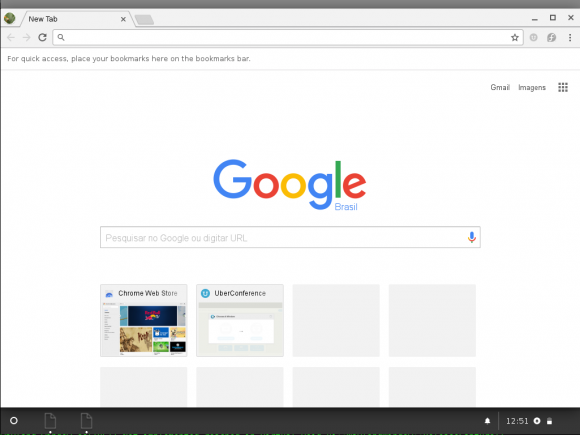

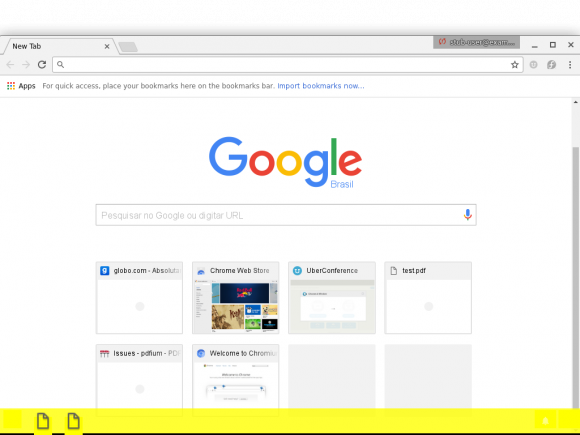

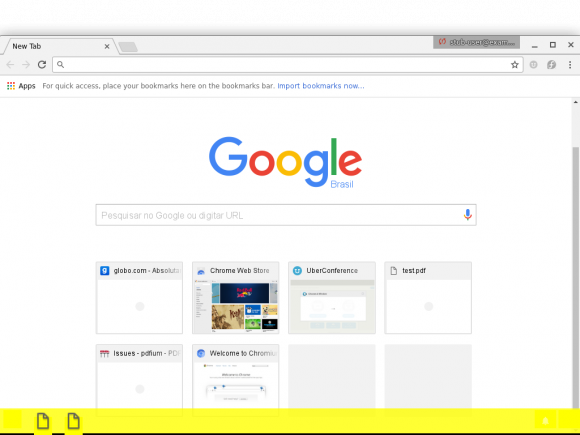

We have reached a point where we can show Chrome Ozone/Mus on desktop Linux, on using both X11 and Wayland backends, and here is how it is looking like today:

Wayland:

X11:

The –mus and –ozone-platform={name} command line parameters control the Chrome configuration. Please note that the same Chrome binary is used.

Some of our next steps for Chromium Mus/Ozone are:

- Continue to fix the windowing features (namely window resize and dragging, as well as drag and drop) when Chromium’s builtin window decorations are used.

- Provide updated yocto builds on Igalia’s meta-browser fork.

- Support newer shell protocols like XDG v6, supported by Fedora 25.

- Ensure no feature losses when compared to stock Chromium X11/Linux.

- Ensure there is no performance penalties when compared to stock Chromium X11/Linux.

- Start to upstream some of the changes.

We are also considering providing prebuilt binaries, so that earlier adopters can test the status.

This project is sponsored by Renesas Electronics …

… and is being performed by Igalian hacker Maksim Sisov and Antonio Gomes (me) on behalf of Igalia, being Frederic Wang an emeritus contributor.