First steps with Zephyr (II)

In the previous post we set up a Zephyr development environment and checked that we could build applications for multiple different targets. In this one we'll work on a sample application that we can use to showcase a few Zephyr features and as a template for other applications with a similar workflow.

We'll simulate a real work scenario and develop a firmware

for a hardware board (in this example it'll be

a Raspberry

Pi Pico 2W) and we'll set up a development workflow that

supports the native_sim target, so we can do most

of the programming and software prototyping on a simulated

environment without having to rely on the

hardware.

When developing for new hardware, it's a common practice

that the software teams need to start working on firmware

and drivers before the hardware is available, so the initial

stages of software development for new silicon and boards is

often tested on software or hardware emulators.

Then, after the prototyping is done we can deploy and test the

firmare on the real board. We'll see how we can do a simple

behavioral model of some of the devices we'll use in the final

hardware setup and how we can leverage this workflow to

unit-test and refine the firmware.

This post is a walkthrough of the whole application. You can find the code here.

Application description

The application we'll build and run on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2W will basically just listen for a button press. When the button is pressed the app will enqueue some work to be done by a processing thread and the result will be published via I2C for a controller to request. At the same time, it will configure two serial consoles, one for message logging and another one for a command shell that can be used for testing and debugging.

These are the main features we'll cover with this experiment:

- Support for multiple targets.

- Target-specific build and hardware configuration.

- Logging.

- Multiple console output.

- Zephyr shell with custom commands.

- Device emulation.

- GPIO handling.

- I2C target handling.

- Thread synchronization and message-passing.

- Deferred work (bottom halves).

Hardware setup

Besides the target board and the development machine, we'll be using a Linux-based development board that we can use to communicate with the Zephyr board via I2C. Anything will do here, I used a very old Raspberry Pi Model B that I had lying around.

The only additional peripheral we'll need is a physical button connected to a couple of board pins. If we don't have any, a jumper cable and a steady pulse will also work. Optionally, to take full advantage of the two serial ports, a USB - TTL UART converter will be useful. Here's how the full setup looks like:

+--------------------------+

| | Eth

| Raspberry Pi |---------------+

| | |

+--------------------------+ |

6 5 3 |

| | | |

| I2C I2C / |

GND SCL SDA __/ __ |

| | | | GND |

| | | | | |

18 7 6 4 38 |

+--------------------------+ +-------------+

| | USB | Development |

| Raspberry Pi Pico 2W |------------| machine |

| | +-------------+

+--------------------------+ |

13 12 11 |

| | | |

GND UART1 UART1 |

| RX TX |

| | | |

+-----------------+ USB |

| USB - UART TTL |------------------+

| converter |

+-----------------+

For additional info on how to set up the Linux-based Raspberry Pi, see the appendix at the end.

Setting up the application files

Before we start coding we need to know how we'll structure the application. There are certain conventions and file structure that the build system expects to find under certain scenarios. This is how we'll structure the application (test_rpi):

test_rpi

├── boards

│ ├── native_sim_64.conf

│ ├── native_sim_64.overlay

│ ├── rpi_pico2_rp2350a_m33.conf

│ └── rpi_pico2_rp2350a_m33.overlay

├── CMakeLists.txt

├── Kconfig

├── prj.conf

├── README.rst

└── src

├── common.h

├── emul.c

├── main.c

└── processing.cSome of the files there we already know from

the previous

post: CMakeLists.txt

and prj.conf. All the application code will be in

the src directory, and we can structure it as we

want as long as we tell the build system about the files we

want to compile. For this application, the main code will be

in main.c, processing.c will contain

the code of the processing thread, and emul.c

will keep everything related to the device emulation for

the native_sim target and will be compiled only

when we build for that target. We describe this to the build

system through the contents of CMakeLists.txt:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.20.0)

find_package(Zephyr REQUIRED HINTS $ENV{ZEPHYR_BASE})

project(test_rpi)

target_sources(app PRIVATE src/main.c src/processing.c)

target_sources_ifdef(CONFIG_BOARD_NATIVE_SIM app PRIVATE src/emul.c)In prj.conf we'll put the general Zephyr

configuration options for this application. Note that inside

the boards directory there are two additional

.conf files. These are target-specific options that will be

merged to the common ones in prj.conf depending

on the target we choose to build for.

Normally, most of the options we'll put in the .conf files will be already defined, but we can also define application-specific config options that we can later reference in the .conf files and the code. We can define them in the application-specific Kconfig file. The build system will it pick up as the main Kconfig file if it exists. For this application we'll define one additional config option that we'll use to configure the log level for the program, so this is how Kconfig will look like:

config TEST_RPI_LOG_LEVEL

int "Default log level for test_rpi"

default 4

source "Kconfig.zephyr"Here we're simply prepending a config option before all the rest of the main Zephyr Kconfig file. We'll see how to use this option later.

Finally, the boards directory also contains

target-specific overlay files. These are regular device tree

overlays which are normally used to configure the

hardware. More about that in a while.

Main application architecture

The application flow is structured in two main threads: the

main

thread

and an additional processing thread that does its work

separately. The main thread runs the application entry point

(the main() function) and does all the software

and device set up. Normally it doesn't need to do anything

more, we can use it to start other threads and have them do

the rest of the work while the main thread sits idle, but in

this case we're doing some work with it instead of creating an

additional thread for that. Regarding the processing thread,

we can think of it as "application code" that runs on its

own and provides a simple interface to interact with the rest

of the system1.

Once the main thread has finished all the initialization process (creating threads, setting up callbacks, configuring devices, etc.) it sits in an infinite loop waiting for messages in a message queue. These messages are sent by the processing thread, which also runs in a loop waiting for messages in another queue. The messages to the processing thread are sent, as a result of a button press, by the GPIO ISR callback registered (actually, by the bottom half triggered by it and run by a workqueue thread). Ignoring the I2C part for now, this is how the application flow would look like:

Main thread Processing thread Workqueue thread GPIO ISR

| | | |

| | |<--------------| |

| |<------------------| | (1) |

| | | (2) | |

|<----------------| | | |

| | (3) | | |

| | | |Once the button press is detected, the GPIO ISR calls a callback we registered in the main setup code. The callback defers the work (1) through a workqueue (we'll see why later), which sends some data to the processing thread (2). The data it'll send is just an integer: the current uptime in seconds. The processing thread will then do some processing using that data (convert it to a string) and will send the processed data to the main thread (3). Let's take a look at the code that does all this.

Thread creation

As we mentioned, the main thread will be responsible for, among other tasks, spawning other threads. In our example it will create only one additional thread.

#include <zephyr/kernel.h>

#define THREAD_STACKSIZE 2048

#define THREAD_PRIORITY 10

K_THREAD_STACK_DEFINE(processing_stack, THREAD_STACKSIZE);

struct k_thread processing_thread;

int main(void)

{

[...]

/* Thread initialization */

k_thread_create(&processing_thread, processing_stack,

THREAD_STACKSIZE, data_process,

&in_msgq, &out_msgq, NULL,

THREAD_PRIORITY, 0, K_FOREVER);

k_thread_name_set(&processing_thread, "processing");

k_thread_start(&processing_thread);We'll see what the data_process() function does

in a while. For now, notice we're passing two message queues,

one for input and one for output, as parameters for that

function. These will be used as the interface to connect the

processing thread to the rest of the firmware.

GPIO handling

Zephyr's device tree support greatly simplifies device handling and makes it really easy to parameterize and handle device operations in an abstract way. In this example, we define and reference the GPIO for the button in our setup using a platform-independent device tree node:

#define ZEPHYR_USER_NODE DT_PATH(zephyr_user)

const struct gpio_dt_spec button = GPIO_DT_SPEC_GET_OR(

ZEPHYR_USER_NODE, button_gpios, {0});

This looks for a "button-gpios" property in

the "zephyr,user"

node in the device tree of the target platform and

initializes

a gpio_dt_spec

property containing the GPIO pin information defined in the

device tree. Note that this initialization and the check for

the "zephyr,user" node are static and happen at compile time

so, if the node isn't found, the error will be caught by the

build process.

This is how the node is defined for the Raspberry Pi Pico 2W:

/ {

[...]

zephyr,user {

button-gpios = <&gpio0 2 (GPIO_ACTIVE_LOW | GPIO_PULL_UP)>;

};

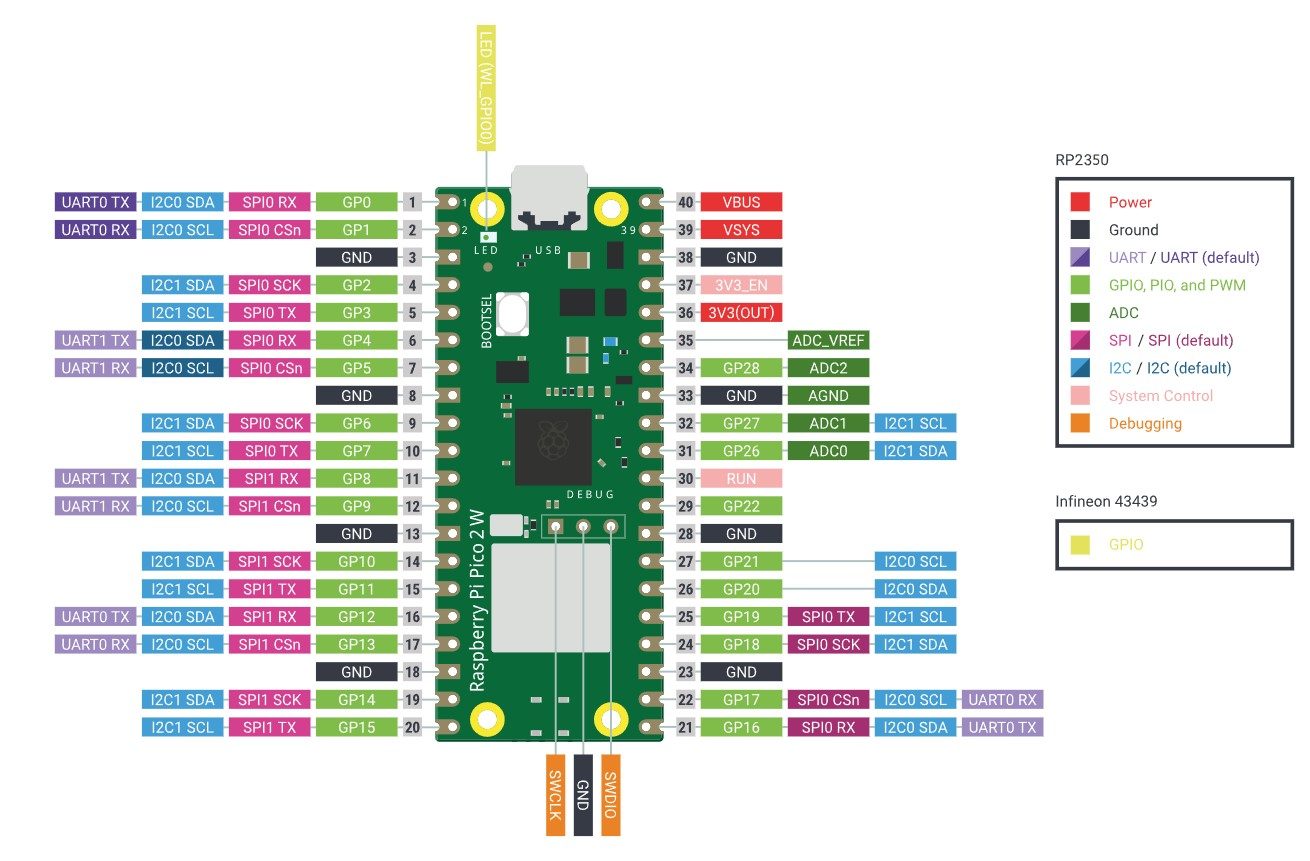

};This defines the GPIO to be used as the second GPIO from bank 0, it'll be set up with an internal pull-up resistor and will be active-low. See the device tree GPIO API for details on the specification format. In the board, that GPIO is routed to pin 4:

Now we'll use the GPIO API to configure the GPIO as defined and to add a callback that will run when the button is pressed:

if (!gpio_is_ready_dt(&button)) {

LOG_ERR("Error: button device %s is not ready",

button.port->name);

return 0;

}

ret = gpio_pin_configure_dt(&button, GPIO_INPUT);

if (ret != 0) {

LOG_ERR("Error %d: failed to configure %s pin %d",

ret, button.port->name, button.pin);

return 0;

}

ret = gpio_pin_interrupt_configure_dt(&button,

GPIO_INT_EDGE_TO_ACTIVE);

if (ret != 0) {

LOG_ERR("Error %d: failed to configure interrupt on %s pin %d",

ret, button.port->name, button.pin);

return 0;

}

gpio_init_callback(&button_cb_data, button_pressed, BIT(button.pin));

gpio_add_callback(button.port, &button_cb_data);We're configuring the pin as an input and then we're enabling interrupts for it when it goes to logical level "high". In this case, since we defined it as active-low, the interrupt will be triggered when the pin transitions from the stable pulled-up voltage to ground.

Finally, we're initializing and adding a callback function that will be called by the ISR when it detects that this GPIO goes active. We'll use this callback to start an action from a user event. The specific interrupt handling is done by the target-specific device driver2 and we don't have to worry about that, our code can remain device-independent.

NOTE: The callback we'll define is meant as a simple exercise for illustrative purposes. Zephyr provides an input subsystem to handle cases like this properly.

What we want to do in the callback is to send a message to

the processing thread. The communication input channel to the

thread is the in_msgq message queue, and the data

we'll send is a simple 32-bit integer with the number of

uptime seconds. But before doing that, we'll first de-bounce

the button press using a simple idea: to schedule the message

delivery to a

workqueue

thread:

/*

* Deferred irq work triggered by the GPIO IRQ callback

* (button_pressed). This should run some time after the ISR, at which

* point the button press should be stable after the initial bouncing.

*

* Checks the button status and sends the current system uptime in

* seconds through in_msgq if the the button is still pressed.

*/

static void debounce_expired(struct k_work *work)

{

unsigned int data = k_uptime_seconds();

ARG_UNUSED(work);

if (gpio_pin_get_dt(&button))

k_msgq_put(&in_msgq, &data, K_NO_WAIT);

}

static K_WORK_DELAYABLE_DEFINE(debounce_work, debounce_expired);

/*

* Callback function for the button GPIO IRQ.

* De-bounces the button press by scheduling the processing into a

* workqueue.

*/

void button_pressed(const struct device *dev, struct gpio_callback *cb,

uint32_t pins)

{

k_work_reschedule(&debounce_work, K_MSEC(30));

}That way, every unwanted oscillation will cause a

re-scheduling of the message delivery (replacing any prior

scheduling). debounce_expired will eventually

read the GPIO status and send the message.

Thread synchronization and messaging

As I mentioned earlier, the interface with the processing

thread consists on two message queues, one for input and one for

output. These are defined statically with

the K_MSGQ_DEFINE macro:

#define PROC_MSG_SIZE 8

K_MSGQ_DEFINE(in_msgq, sizeof(int), 1, 1);

K_MSGQ_DEFINE(out_msgq, PROC_MSG_SIZE, 1, 1);Both queues have space to hold only one message each. For the input queue (the one we'll use to send messages to the processing thread), each message will be one 32-bit integer. The messages of the output queue (the one the processing thread will use to send messages) are 8 bytes long.

Once the main thread is done initializing everything, it'll stay in an infinite loop waiting for messages from the processing thread. The processing thread will also run a loop waiting for incoming messages in the input queue, which are sent by the button callback, as we saw earlier, so the message queues will be used both for transferring data and for synchronization. Since the code running in the processing thread is so small, I'll paste it here in its entirety:

static char data_out[PROC_MSG_SIZE];

/*

* Receives a message on the message queue passed in p1, does some

* processing on the data received and sends a response on the message

* queue passed in p2.

*/

void data_process(void *p1, void *p2, void *p3)

{

struct k_msgq *inq = p1;

struct k_msgq *outq = p2;

ARG_UNUSED(p3);

while (1) {

unsigned int data;

k_msgq_get(inq, &data, K_FOREVER);

LOG_DBG("Received: %d", data);

/* Data processing: convert integer to string */

snprintf(data_out, sizeof(data_out), "%d", data);

k_msgq_put(outq, data_out, K_NO_WAIT);

}

}I2C target implementation

Now that we have a way to interact with the program by inputting an external event (a button press), we'll add a way for it to communicate with the outside world: we're going to turn our device into a I2C target that will listen for command requests from a controller and send data back to it. In our setup, the controller will be Linux-based Raspberry Pi, see the diagram in the Hardware setup section above for details on how the boards are connected.

In order to define an I2C target we first need a suitable device defined in the device tree. To abstract the actual target-dependent device, we'll define and use an alias for it that we can redefine for every supported target. For instance, for the Raspberry Pi Pico 2W we define this alias in its device tree overlay:

/ {

[...]

aliases {

i2ctarget = &i2c0;

};Where i2c0 is originally defined like this:

i2c0: i2c@40090000 {

compatible = "raspberrypi,pico-i2c", "snps,designware-i2c";

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <0>;

reg = <0x40090000 DT_SIZE_K(4)>;

resets = <&reset RPI_PICO_RESETS_RESET_I2C0>;

clocks = <&clocks RPI_PICO_CLKID_CLK_SYS>;

interrupts = <36 RPI_PICO_DEFAULT_IRQ_PRIORITY>;

interrupt-names = "i2c0";

status = "disabled";

};and then enabled:

&i2c0 {

clock-frequency = <I2C_BITRATE_STANDARD>;

status = "okay";

pinctrl-0 = <&i2c0_default>;

pinctrl-names = "default";

};So now in the code we can reference

the i2ctarget alias to load the device info and

initialize it:

/*

* Get I2C device configuration from the devicetree i2ctarget alias.

* Check node availability at buid time.

*/

#define I2C_NODE DT_ALIAS(i2ctarget)

#if !DT_NODE_HAS_STATUS_OKAY(I2C_NODE)

#error "Unsupported board: i2ctarget devicetree alias is not defined"

#endif

const struct device *i2c_target = DEVICE_DT_GET(I2C_NODE);To register the device as a target, we'll use

the i2c_target_register()

function, which takes the loaded device tree device and an

I2C target configuration (struct

i2c_target_config) containing the I2C

address we choose for it and a set of callbacks for all the

possible events. It's in these callbacks where we'll define the

target's functionality:

#define I2C_ADDR 0x60

[...]

static struct i2c_target_callbacks target_callbacks = {

.write_requested = write_requested_cb,

.write_received = write_received_cb,

.read_requested = read_requested_cb,

.read_processed = read_processed_cb,

.stop = stop_cb,

};

[...]

int main(void)

{

struct i2c_target_config target_cfg = {

.address = I2C_ADDR,

.callbacks = &target_callbacks,

};

if (i2c_target_register(i2c_target, &target_cfg) < 0) {

LOG_ERR("Failed to register target");

return -1;

}Each of those callbacks will be called as a response from an event started by the controller. Depending on how we want to define the target we'll need to code the callbacks to react appropriately to the controller requests. For this application we'll define a register that the controller can read to get a timestamp (the firmware uptime in seconds) from the last time the button was pressed. The number will be received as an 8-byte ASCII string.

If the controller is the Linux-based Raspberry Pi, we can use the i2c-tools to poll the target and read from it:

# Scan the I2C bus:

$ i2cdetect -y 0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f

00: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

10: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

20: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

30: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

40: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

50: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

60: 60 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

70: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

# I2C bus 0: issue command 0 (read uptime) on device 0x60:

# - Send byte 0 to device with address 0x60

# - Read back 8 bytes

$ i2ctransfer -y 0 w1@0x60 0 r8

0x36 0x33 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

We basically want the device to react when the controller sends a write request (to select the register and prepare the data), when it sends a read request (to send the data bytes back to the controller) and when it sends a stop condition.

To handle the data to be sent, the I2C callback functions manage an internal buffer that will hold the string data to send to the controller, and we'll load this buffer with the contents of a source buffer that's updated every time the main thread receives data from the processing thread (a double-buffer scheme). Then, when we program an I2C transfer we walk this internal buffer sending each byte to the controller as we receive read requests. When the transfer finishes or is aborted, we reload the buffer and rewind it for the next transfer:

typedef enum {

I2C_REG_UPTIME,

I2C_REG_NOT_SUPPORTED,

I2C_REG_DEFAULT = I2C_REG_UPTIME

} i2c_register_t;

/* I2C data structures */

static char i2cbuffer[PROC_MSG_SIZE];

static int i2cidx = -1;

static i2c_register_t i2creg = I2C_REG_DEFAULT;

[...]

/*

* Callback called on a write request from the controller.

*/

int write_requested_cb(struct i2c_target_config *config)

{

LOG_DBG("I2C WRITE start");

return 0;

}

/*

* Callback called when a byte was received on an ongoing write request

* from the controller.

*/

int write_received_cb(struct i2c_target_config *config, uint8_t val)

{

LOG_DBG("I2C WRITE: 0x%02x", val);

i2creg = val;

if (val == I2C_REG_UPTIME)

i2cidx = -1;

return 0;

}

/*

* Callback called on a read request from the controller.

* If it's a first read, load the output buffer contents from the

* current contents of the source data buffer (str_data).

*

* The data byte sent to the controller is pointed to by val.

* Returns:

* 0 if there's additional data to send

* -ENOMEM if the byte sent is the end of the data transfer

* -EIO if the selected register isn't supported

*/

int read_requested_cb(struct i2c_target_config *config, uint8_t *val)

{

if (i2creg != I2C_REG_UPTIME)

return -EIO;

LOG_DBG("I2C READ started. i2cidx: %d", i2cidx);

if (i2cidx < 0) {

/* Copy source buffer to the i2c output buffer */

k_mutex_lock(&str_data_mutex, K_FOREVER);

strncpy(i2cbuffer, str_data, PROC_MSG_SIZE);

k_mutex_unlock(&str_data_mutex);

}

i2cidx++;

if (i2cidx == PROC_MSG_SIZE) {

i2cidx = -1;

return -ENOMEM;

}

*val = i2cbuffer[i2cidx];

LOG_DBG("I2C READ send: 0x%02x", *val);

return 0;

}

/*

* Callback called on a continued read request from the

* controller. We're implementing repeated start semantics, so this will

* always return -ENOMEM to signal that a new START request is needed.

*/

int read_processed_cb(struct i2c_target_config *config, uint8_t *val)

{

LOG_DBG("I2C READ continued");

return -ENOMEM;

}

/*

* Callback called on a stop request from the controller. Rewinds the

* index of the i2c data buffer to prepare for the next send.

*/

int stop_cb(struct i2c_target_config *config)

{

i2cidx = -1;

LOG_DBG("I2C STOP");

return 0;

}

int main(void)

{

[...]

while (1) {

char buffer[PROC_MSG_SIZE];

k_msgq_get(&out_msgq, buffer, K_FOREVER);

LOG_DBG("Received: %s", buffer);

k_mutex_lock(&str_data_mutex, K_FOREVER);

strncpy(str_data, buffer, PROC_MSG_SIZE);

k_mutex_unlock(&str_data_mutex);

}Device emulation

The application logic is done at this point, and we were careful to write it in a platform-agnostic way. As mentioned earlier, all the target-specific details are abstracted away by the device tree and the Zephyr APIs. Although we're developing with a real deployment board in mind, it's very useful to be able to develop and test using a behavioral model of the hardware that we can program to behave as close to the real hardware as we need and that we can run on our development machine without the cost and restrictions of the real hardware.

To do this, we'll rely on the native_sim board3, which implements the core OS

services on top of a POSIX compatibility layer, and we'll add

code to simulate the button press and the I2C

requests.

Emulating a button press

We'll use

the gpio_emul

driver as a base for our emulated

button. The native_sim device tree already defines

an emulated GPIO bank for this:

gpio0: gpio_emul {

status = "okay";

compatible = "zephyr,gpio-emul";

rising-edge;

falling-edge;

high-level;

low-level;

gpio-controller;

#gpio-cells = <2>;

};So we can define the GPIO to use for our button in the native_sim board overlay:

/ {

[...]

zephyr,user {

button-gpios = <&gpio0 0 GPIO_ACTIVE_HIGH>;

};

};We'll model the button press as a four-phase event consisting

on an initial status change caused by the press, then a

semi-random rebound phase, then a phase of signal

stabilization after the rebounds stop, and finally a button

release. Using the gpio_emul API it'll look like

this:

/*

* Emulates a button press with bouncing.

*/

static void button_press(void)

{

const struct device *dev = device_get_binding(button.port->name);

int n_bounces = sys_rand8_get() % 10;

int state = 1;

int i;

/* Press */

gpio_emul_input_set(dev, 0, state);

/* Bouncing */

for (i = 0; i < n_bounces; i++) {

state = state ? 0: 1;

k_busy_wait(1000 * (sys_rand8_get() % 10));

gpio_emul_input_set(dev, 0, state);

}

/* Stabilization */

gpio_emul_input_set(dev, 0, 1);

k_busy_wait(100000);

/* Release */

gpio_emul_input_set(dev, 0, 0);

}The driver will take care of checking if the state changes need to raise interrupts, depending on the GPIO configuration, and will trigger the registered callback that we defined earlier.

Emulating an I2C controller

As with the button emulator, we'll rely on an existing

emulated device driver for

this: i2c_emul. Again,

the device tree for the target already defines the node we

need:

i2c0: i2c@100 {

status = "okay";

compatible = "zephyr,i2c-emul-controller";

clock-frequency = <I2C_BITRATE_STANDARD>;

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <0>;

#forward-cells = <1>;

reg = <0x100 4>;

};So we can define a machine-independent alias that we can reference in the code:

/ {

aliases {

i2ctarget = &i2c0;

};The events we need to emulate are the requests sent by the

controller: READ start, WRITE start and STOP. We can define

these based on

the i2c_transfer()

API function which will, in this case, use

the i2c_emul

driver implementation to simulate the transfer. As in the

GPIO emulation case, this will trigger the appropriate

callbacks. The implementation of our controller requests looks

like this:

/*

* A real controller may want to continue reading after the first

* received byte. We're implementing repeated-start semantics so we'll

* only be sending one byte per transfer, but we need to allocate space

* for an extra byte to process the possible additional read request.

*/

static uint8_t emul_read_buf[2];

/*

* Emulates a single I2C READ START request from a controller.

*/

static uint8_t *i2c_emul_read(void)

{

struct i2c_msg msg;

int ret;

msg.buf = emul_read_buf;

msg.len = sizeof(emul_read_buf);

msg.flags = I2C_MSG_RESTART | I2C_MSG_READ;

ret = i2c_transfer(i2c_target, &msg, 1, I2C_ADDR);

if (ret == -EIO)

return NULL;

return emul_read_buf;

}

static void i2c_emul_write(uint8_t *data, int len)

{

struct i2c_msg msg;

/*

* NOTE: It's not explicitly said anywhere that msg.buf can be

* NULL even if msg.len is 0. The behavior may be

* driver-specific and prone to change so we're being safe here

* by using a 1-byte buffer.

*/

msg.buf = data;

msg.len = len;

msg.flags = I2C_MSG_WRITE;

i2c_transfer(i2c_target, &msg, 1, I2C_ADDR);

}

/*

* Emulates an explicit I2C STOP sent from a controller.

*/

static void i2c_emul_stop(void)

{

struct i2c_msg msg;

uint8_t buf = 0;

/*

* NOTE: It's not explicitly said anywhere that msg.buf can be

* NULL even if msg.len is 0. The behavior may be

* driver-specific and prone to change so we're being safe here

* by using a 1-byte buffer.

*/

msg.buf = &buf;

msg.len = 0;

msg.flags = I2C_MSG_WRITE | I2C_MSG_STOP;

i2c_transfer(i2c_target, &msg, 1, I2C_ADDR);

}Now we can define a complete request for an "uptime read" operation in terms of these primitives:

/*

* Emulates an I2C "UPTIME" command request from a controller using

* repeated start.

*/

static void i2c_emul_uptime(const struct shell *sh, size_t argc, char **argv)

{

uint8_t buffer[PROC_MSG_SIZE] = {0};

i2c_register_t reg = I2C_REG_UPTIME;

int i;

i2c_emul_write((uint8_t *)®, 1);

for (i = 0; i < PROC_MSG_SIZE; i++) {

uint8_t *b = i2c_emul_read();

if (b == NULL)

break;

buffer[i] = *b;

}

i2c_emul_stop();

if (i == PROC_MSG_SIZE) {

shell_print(sh, "%s", buffer);

} else {

shell_print(sh, "Transfer error");

}

}Ok, so now that we have implemented all the emulated operations we needed, we need a way to trigger them on the emulated environment. The Zephyr shell is tremendously useful for cases like this.

Shell commands

The shell module in Zephyr has a lot of useful features that we can use for debugging. It's quite extensive and talking about it in detail is out of the scope of this post, but I'll show how simple it is to add a few custom commands to trigger the button presses and the I2C controller requests from a console. In fact, for our purposes, the whole thing is as simple as this:

SHELL_CMD_REGISTER(buttonpress, NULL, "Simulates a button press", button_press);

SHELL_CMD_REGISTER(i2cread, NULL, "Simulates an I2C read request", i2c_emul_read);

SHELL_CMD_REGISTER(i2cuptime, NULL, "Simulates an I2C uptime request", i2c_emul_uptime);

SHELL_CMD_REGISTER(i2cstop, NULL, "Simulates an I2C stop request", i2c_emul_stop);We'll enable these commands only when building for

the native_sim board. With the configuration

provided, once we run the application we'll have the log

output in stdout and the shell UART connected to a pseudotty,

so we can access it in a separate terminal and run these

commands while we see the output in the terminal where we ran

the application:

$ ./build/zephyr/zephyr.exe

WARNING: Using a test - not safe - entropy source

uart connected to pseudotty: /dev/pts/16

*** Booting Zephyr OS build v4.1.0-6569-gf4a0beb2b7b1 ***

# In another terminal

$ screen /dev/pts/16

uart:~$

uart:~$ help

Please press the <Tab> button to see all available commands.

You can also use the <Tab> button to prompt or auto-complete all commands or its subcommands.

You can try to call commands with <-h> or <--help> parameter for more information.

Shell supports following meta-keys:

Ctrl + (a key from: abcdefklnpuw)

Alt + (a key from: bf)

Please refer to shell documentation for more details.

Available commands:

buttonpress : Simulates a button press

clear : Clear screen.

device : Device commands

devmem : Read/write physical memory

Usage:

Read memory at address with optional width:

devmem <address> [<width>]

Write memory at address with mandatory width and value:

devmem <address> <width> <value>

help : Prints the help message.

history : Command history.

i2cread : Simulates an I2C read request

i2cstop : Simulates an I2C stop request

i2cuptime : Simulates an I2C uptime request

kernel : Kernel commands

rem : Ignore lines beginning with 'rem '

resize : Console gets terminal screen size or assumes default in case

the readout fails. It must be executed after each terminal

width change to ensure correct text display.

retval : Print return value of most recent command

shell : Useful, not Unix-like shell commands.To simulate a button press (ie. capture the current uptime):

uart:~$ buttonpressAnd the log output should print the enabled debug messages:

[00:00:06.300,000] <dbg> test_rpi: data_process: Received: 6

[00:00:06.300,000] <dbg> test_rpi: main: Received: 6If we now simulate an I2C uptime command request we should get the captured uptime as a string:

uart:~$ i2cuptime

6We can check the log to see how the I2C callbacks ran:

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: write_requested_cb: I2C WRITE start

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: write_received_cb: I2C WRITE: 0x00

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: stop_cb: I2C STOP

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ started. i2cidx: -1

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ send: 0x36

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_processed_cb: I2C READ continued

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ started. i2cidx: 0

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ send: 0x00

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_processed_cb: I2C READ continued

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ started. i2cidx: 1

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ send: 0x00

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_processed_cb: I2C READ continued

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ started. i2cidx: 2

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ send: 0x00

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_processed_cb: I2C READ continued

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ started. i2cidx: 3

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ send: 0x00

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_processed_cb: I2C READ continued

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ started. i2cidx: 4

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ send: 0x00

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_processed_cb: I2C READ continued

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ started. i2cidx: 5

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ send: 0x00

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_processed_cb: I2C READ continued

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ started. i2cidx: 6

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_requested_cb: I2C READ send: 0x00

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: read_processed_cb: I2C READ continued

[00:01:29.400,000] <dbg> test_rpi: stop_cb: I2C STOPAppendix: Linux set up on the Raspberry Pi

This is the process I followed to set up a Linux system on a Raspberry Pi (very old, model 1 B). There are plenty of instructions for this on the Web, and you can probably just pick up a pre-packaged and pre-configured Raspberry Pi OS and get done with it faster, so I'm adding this here for completeness and because I want to have a finer grained control of what I put into it.

The only harware requirement is an SD card with two partitions: a small (~50MB) FAT32 boot partition and the rest of the space for the rootfs partition, which I formatted as ext4. The boot partition should contain a specific set of configuration files and binary blobs, as well as the kernel that we'll build and the appropriate device tree binary. See the official docs for more information on the boot partition contents and this repo for the binary blobs. For this board, the minimum files needed are:

- bootcode.bin: the second-stage bootloader, loaded by the first-stage bootloader in the BCM2835 ROM. Run by the GPU.

- start.elf: GPU firmware, starts the ARM CPU.

- fixup.dat: needed by start.elf. Used to configure the SDRAM.

- kernel.img: this is the kernel image we'll build.

- dtb files and overlays.

And, optionally but very recommended:

- config.txt: bootloader configuration.

- cmdline.txt: kernel command-line parameters.

In practice, pretty much all Linux setups will also have

these files. For our case we'll need to add one additional

config entry to the config.txt file in order to

enable the I2C bus:

dtparam=i2c_arm=onOnce we have the boot partition populated with the basic required files (minus the kernel and dtb files), the two main ingredients we need to build now are the kernel image and the root filesystem.

Building a Linux kernel for the Raspberry Pi

Main reference: Raspberry Pi docs

There's nothing non-standard about how we'll generate this

kernel image, so you can search the Web for references on how

the process works if you need to. The only things to take into

account is that we'll pick

the Raspberry

Pi kernel instead of a vanilla mainline kernel. I also

recommend getting the arm-linux-gnueabi

cross-toolchain

from kernel.org.

After installing the toolchain and cloning the repo, we just have to run the usual commands to configure the kernel, build the image, the device tree binaries, the modules and have the modules installed in a specific directory, but first we'll add some extra config options:

cd kernel_dir

KERNEL=kernel

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabi- bcmrpi_defconfigWe'll need to add at least ext4 builtin support so that the

kernel can mount the rootfs, and I2C support for our

experiments, so we need to edit .config, add

these:

CONFIG_EXT4_FS=y

CONFIG_I2C=yAnd run the olddefconfig target. Then we can

proceed with the rest of the build steps:

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabi- olddefconfig

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabi- zImage modules dtbs -j$(nproc)

mkdir modules

make ARCH=arm CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabi- INSTALL_MOD_PATH=./modules modules_installNow we need to copy the kernel and the dtbs to the boot partition of the sd card:

cp arch/arm/boot/zImage /path_to_boot_partition_mountpoint/kernel.img

cp arch/arm/boot/dts/broadcom/*.dtb /path_to_boot_partition_mountpoint

mkdir /path_to_boot_partition_mountpoint/overlays

cp arch/arm/boot/dts/overlays/*.dtb /path_to_boot_partition_mountpoint/overlays

(we really only need the dtb for this particular board, but anyway).

Setting up a Debian rootfs

There are many ways to do this, but I normally use the classic debootstrap to build Debian rootfss. Since I don't always know which packages I'll need to install ahead of time, the strategy I follow is to build a minimal image with the bare minimum requirements and then boot it either on a virtual machine or in the final target and do the rest of the installation and setup there. So for the initial setup I'll only include the openssh-server package:

mkdir bookworm_armel_raspi

sudo debootstrap --arch armel --include=openssh-server bookworm \

bookworm_armel_raspi http://deb.debian.org/debian

# Remove the root password

sudo sed -i '/^root/ { s/:x:/::/ }' bookworm_armel_raspi/etc/passwd

# Create a pair of ssh keys and install them to allow passwordless

# ssh logins

cd ~/.ssh

ssh-keygen -f raspi

sudo mkdir bookworm_armel_raspi/root/.ssh

cat raspi.pub | sudo tee bookworm_armel_raspi/root/.ssh/authorized_keys

Now we'll copy the kernel modules to the rootfs. From the kernel directory, and based on the build instructions above:

cd kernel_dir

sudo cp -fr modules/lib/modules /path_to_rootfs_mountpoint/lib

If your distro provides qemu static binaries (eg. Debian: qemu-user-static), it's a good idea to copy the qemu binary to the rootfs so we can mount it locally and run apt-get on it:

sudo cp /usr/bin/qemu-arm-static bookworm_armel_raspi/usr/bin

Otherwise, we can boot a kernel on qemu and load the rootfs there to continue the installation. Next we'll create and populate the filesystem image, then we can boot it on qemu for additional tweaks or dump it into the rootfs partition of the SD card:

# Make rootfs image

fallocate -l 2G bookworm_armel_raspi.img

sudo mkfs -t ext4 bookworm_armel_raspi.img

sudo mkdir /mnt/rootfs

sudo mount -o loop bookworm_armel_raspi.img /mnt/rootfs/

sudo cp -a bookworm_armel_raspi/* /mnt/rootfs/

sudo umount /mnt/rootfs

To copy the rootfs to the SD card:

sudo dd if=bookworm_armel_raspi.img of=/dev/sda2 bs=4M(Substitute /dev/sda2 for the sd card rootfs

partition in your system).

At this point, if we need to do any extra configuration steps we can either:

- Mount the SD card and make the changes there.

- Boot the filesystem image in qemu with a suitable kernel and make the changes in a live system, then dump the changes into the SD card again.

- Boot the board and make the changes there directly. For this we'll need to access the board serial console through its UART pins.

Here are some of the changes I made. First, network

configuration. I'm setting up a dedicated point-to-point

Ethernet link between the development machine (a Linux laptop)

and the Raspberry Pi, with fixed IPs. That means I'll use a

separate subnet for this minimal LAN and that the laptop will

forward traffic between the Ethernet nic and the WLAN

interface that's connected to the Internet. In the rootfs I

added a file

(/etc/systemd/network/20-wired.network) with the

following contents:

[Match]

Name=en*

[Network]

Address=192.168.2.101/24

Gateway=192.168.2.100

DNS=1.1.1.1Where 192.168.2.101 is the address of the board NIC and

192.168.2.100 is the one of the Eth NIC in my laptop. Then,

assuming we have access to the serial console of the board and

we logged in as root, we need to

enable systemd-networkd:

systemctl enable systemd-networkdAdditionally, we need to edit the ssh server configuration to

allow login as root. We can do this by

setting PermitRootLogin yes

in /etc/ssh/sshd_config.

In the development machine, I configured the traffic forwarding to the WLAN interface:

sudo sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

sudo pptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o <wlan_interface> -j MASQUERADEOnce all the configuration is done we should be able to log in as root via ssh:

ssh -i ~/.ssh/raspi root@192.168.2.101In order to issue I2C requests to the Zephyr board, we'll need to load the i2c-dev module at boot time and install the i2c-tools in the Raspberry Pi:

apt-get install i2c-tools

echo "ic2-dev" >> /etc/modules1: Although in this case the thread is a regular kernel thread and runs on the same memory space as the rest of the code, so there's no memory protection. See the User Mode page in the docs for more details.↩

2: As a reference, for the Raspberry Pi Pico 2W, this is where the ISR is registered for enabled GPIO devices, and this is the ISR that checks the pin status and triggers the registered callbacks.↩

3: native_sim_64 in my setup.↩