BUG() statements in the code and rogue DMA access (due to driver or HW issues) are also a common cause. A kernel panic, on the other hand, is the action the kernel takes once an oops is detected – and in most cases, the system is typically rebooted as a consequence of these errors.

Another possible action, though, is to configure the system to attempt a log collection in the face of these issues, in order to have a post-mortem investigation, after a reboot to clean state. And that is where technologies like kdump and pstore come in handy!

Pstore x Kdump – pros and cons

Pstore is a mechanism to have the kernel write some information in a persistent storage backend. The most common scenario is to write the dmesg after an oops condition to the pstore backend, which could be the RAM, a UEFI variable, or even a block device. There are other backends (ACPI ERST tables, for example) and other frontends as well, like the console or ftrace ring buffer, though they’re out of the scope of this introductory post. Kdump on the other hand is a technology in which the kernel jumps to a new kernel (called “crash kernel”) when some (user-configurable) condition is observed, like an oops. The “jump” to the new kernel happens through the kexec kernel mechanism, bypassing the FW initialization, so the crash kernel has complete visibility of the state of the old, “broken” kernel, and is able to collect not only logs, but the full memory image, calledvmcore. Such memory image could be trimmed to remove userspace data and free pages, and it is usually compressed. All of that is configurable, and the details will be discussed in a future blog post.

So, what is the best option? Which one, between pstore and kdump, should be used? As usual in computing (and for everything in life, usually), it depends. The trade-offs here are related to risks involved, which differ between kdump and pstore, the amount of information you want to collect (hence, store!) and the memory / time resources one is willing to spend on that.

vmcore, but even compressed, the data might be multiple GBs, while a compressed kernel dmesg (that can be enhanced with some extra information, detailed below) is in the order of kBs, maybe a few MBs tops.

Finally, the risks are present in both pstore and kdump, though they differ a bit: kdump relies on kexec, which is a fast reboot mechanism that bypasses the FW, for the good and the bad. Kexec is for sure faster and more lightweight than a full firmware reboot, but at the same time, we don’t have a standard protocol for PCIe HW resetting, specially on more common architectures like x86 and ARM, so we need to rely on drivers to proper restart the devices; this may lead to issues in the boot time of the crash kernel, or to HW malfunctioning in such kernel, that could incur in a lost opportunity to collect logs, if the storage device doesn’t work fine without a FW reboot, for example, causing the vmcore saving step to fail.

From the pstore perspective, the mechanism relies on having the broken kernel to write logs to a persistent storage, so this is inherently unsafe; also, backends may be tricky to deal with, the RAM case being very emblematic. Lots of FW implementations either retrain or just purely corrupt the RAM on boot process, so pstore logs saved to RAM might be useless in some systems. UEFI variables are more stable and should be really persistent, but your mileage may vary: some UEFI implementations may not behave properly, or there may be almost no free space to store even a small dmesg in the UEFI area.

All in all, it’s a matter of considering the trade-offs and experimenting. I’ve made a presentation about this topic in the Linux Plumbers 2023, so for the interested readers I suggest you to take a look in the recording! Now, for the sake of experimenting, here comes the kdumpst tool: an automatic log collection tool for Arch Linux and SteamOS that relies on both pstore and kdump!

Presenting kdumpst

Most common Linux distros come with a kdump tool, like kdump-tools for Debian (and Ubuntu), Fedora’s kdump, etc. Arch Linux, on the other hand, is missing some high level utility; the Arch wiki even recommended a manual process for collecting kernel core dumps, setting everything up “by hand”. The lack of tooling is especially felt on SteamOS, the distribution used by Valve’s Steam Deck, which is a port of Arch Linux. An interesting, and important, feature for SteamOS is the ability to collect logs or any information in case of a kernel crash; but how to ponder and choose between kdump or pstore? The Steam Deck has a powerful HW, but “spending” ~250MB of RAM in every boot just to set kdump seems an overkill; so why not take advantage of both? Well, that’s exactly the purpose of kdumpst: to enable users to have a choice and determine in a case-by-case fashion what’s the level of information they wish to have in case of a kernel crash – the more information is desired (avmcore being the gold standard), the more resources are required for that. So, kdumpst by default relies on pstore’s RAM backend (though the UEFI backend is under implementation), but users can change it to kdump mode, so it will pre-reserve some RAM memory and load the crash kernel. The tool also makes use of some sysctl tunings to panic and reboot under some circumstances (oops, hard lockups, etc) and dump extra information on dmesg, like tasks’ state and memory information (through the panic_print tuning) – all of that part of kdumpst custom settings, which can be easily changed by the user.I plan more detailed blog posts to describe the pstore mechanism and how to use it with kdumpst (and even some tricks out of the tool’s scope), and the same for the kdump facility. But it is worth to give here some hints on how to make use of the tool and explore its capabilities on Arch Linux, a “crash course” let’s say :-]

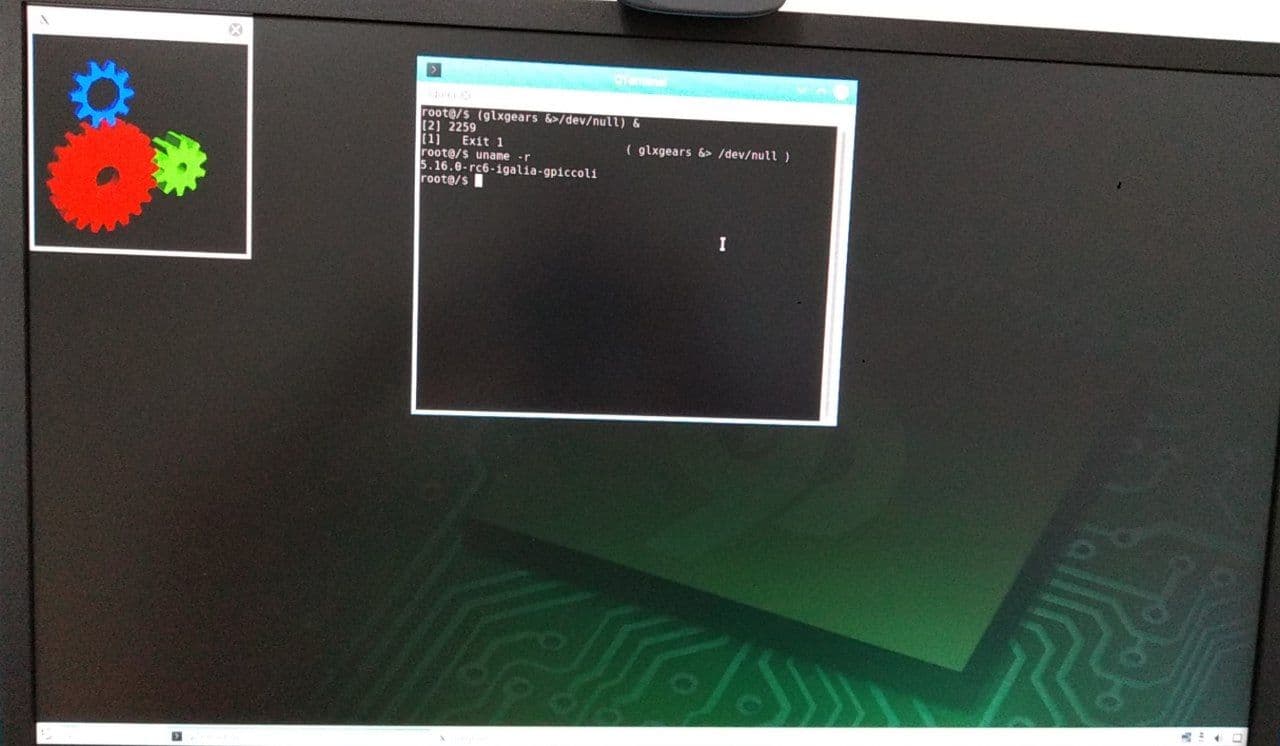

Set-up and experimenting with kdumpst

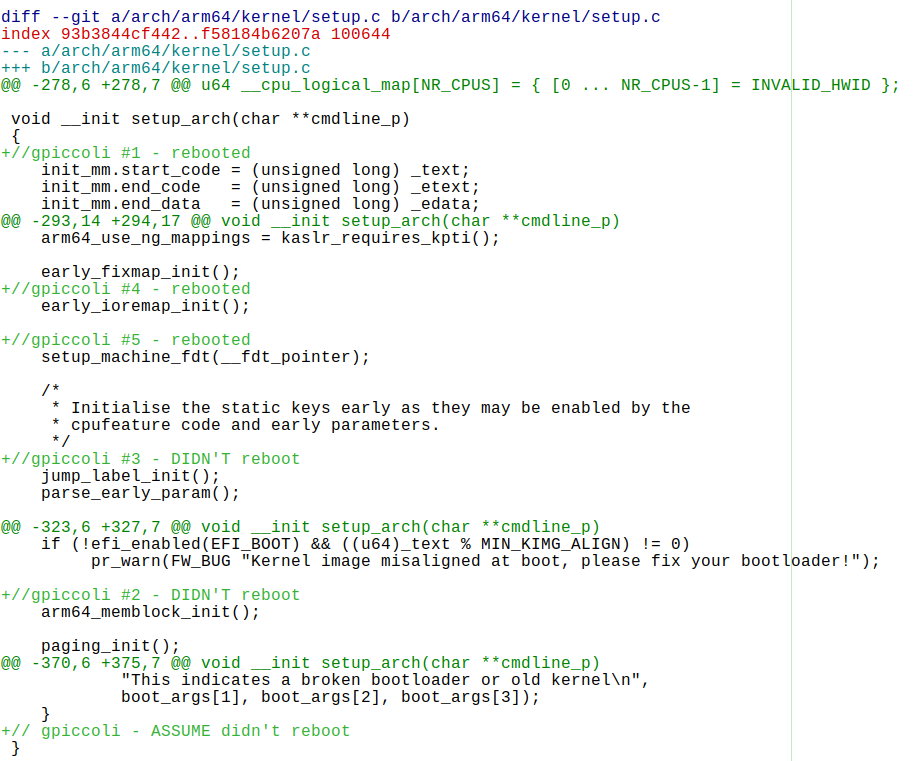

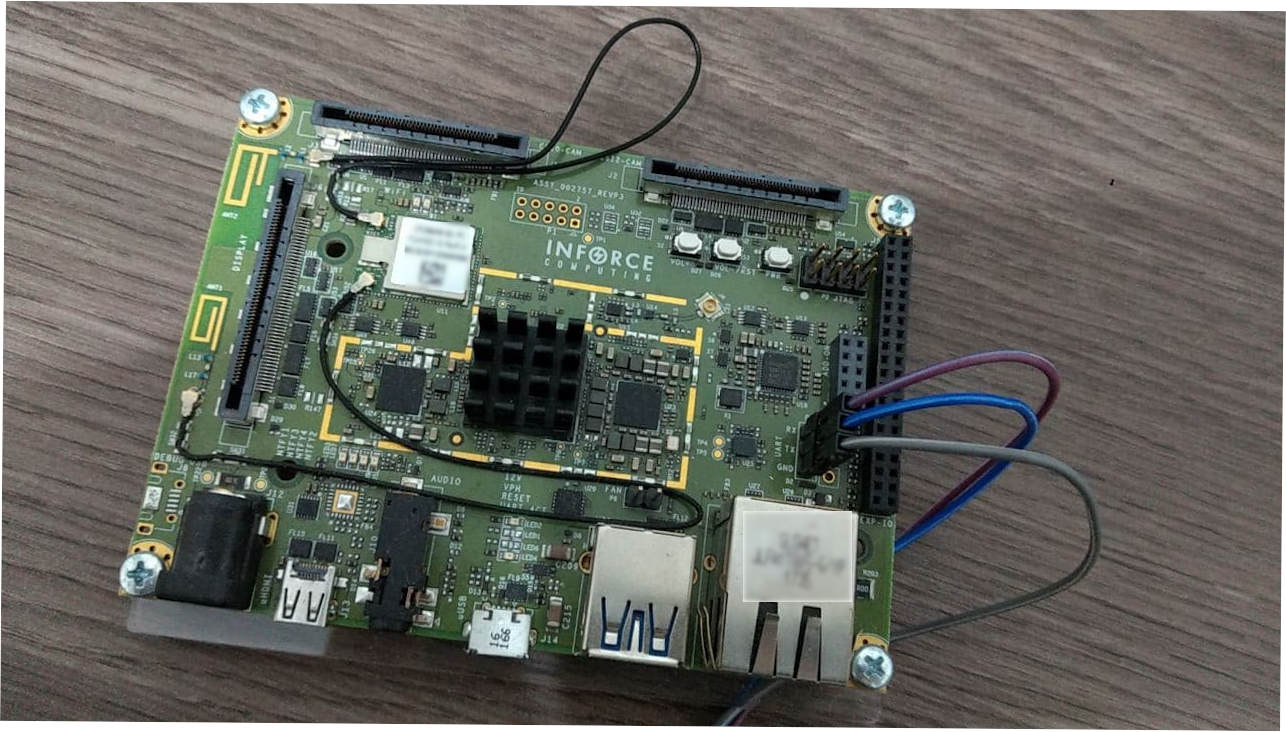

First of all, you should get the kdumpst package from the AUR and install it. After that, you must enable and start its service, by runningsystemctl enable --now kdumpst-init . The default mode of operation for kdumpst is based on pstore with RAM backend, so naturally it’ll try to find a region of memory unused by the kernel. It’s not super common to have a region without allocating it previously, but sometimes due to x86 alignment, or a device-tree setting on ARM boards, it might be available.

If pstore is properly set, a message like the following would show up in the systemd journal:kdumpst: pstore-RAM was loaded successfully.You can check that using the command:

journalctl -b | grep kdumpst.

If pstore RAM mode fails, the tool will automatically attempts kdump, and the following 2 messages should be present in the logs:

kdumpst: kexec won't succeed, no reserved memory in this boot…kdumpst: but we automatically set crashkernel for next boot.

kdumpst: panic kexec loaded successfully.

In both cases (pstore or kdump), if the logs report that kdumpst loaded successfully, the system should be ready for collecting the kernel log in case of a crash event. Testing isn’t a bad idea, so how about triggering a “fake” panic to verify? For that, the next 2 commands should do the trick (run them as root user):echo 1 > /proc/sys/kernel/sysrqecho c > /proc/sysrq-trigger

Be aware that these commands will cause a kernel panic, potentially leading to data corruption, so better to run it on an idle system!The effect should be a reboot; when the system finishes the initialization process, the following entry should be present in the journal:

kdumpst: logs saved in "/home/.steamos/offload/var/kdumpst/logs"

/var/share/kdumpst.d/00-default – one can set various options there, like the default mode (pstore/kdump), the amount of reserved memory for kdump, the directory used to store the logs, record size of pstore, etc. Another configuration file that may be interesting is the sysctl one, at /usr/lib/sysctl.d/20-panic-sysctls.conf, which can be used to fine tune the panic actions for the kernel.

So, hopefully, this short introduction has been helpful for Arch Linux users to start experimenting with kdumpst. If you find any issue, have a suggestion for some improvement, or even submit a contribution, feel free to open an issue in the kdumpst gitlab repo. Thanks for reading and see you soon in the next posts about pstore and kdump!

Hope the read was enjoyable and useful, feel free to leave your comment or ping on IRC (gpiccoli @OFTC/Libera) =]

Hope the read was enjoyable and useful, feel free to leave your comment or ping on IRC (gpiccoli @OFTC/Libera) =]